Anatomy of a Biotech Failure: Part II

learning from the lessons of the graveyard

Last week, age1 published “Anatomy of a Biotech Failure,” a synthesis of case studies in company shutdowns examining scientific, clinical, financial, regulatory, commercial, and operational drivers. But case studies are anecdotal and vulnerable to selective disclosure, limiting inference.

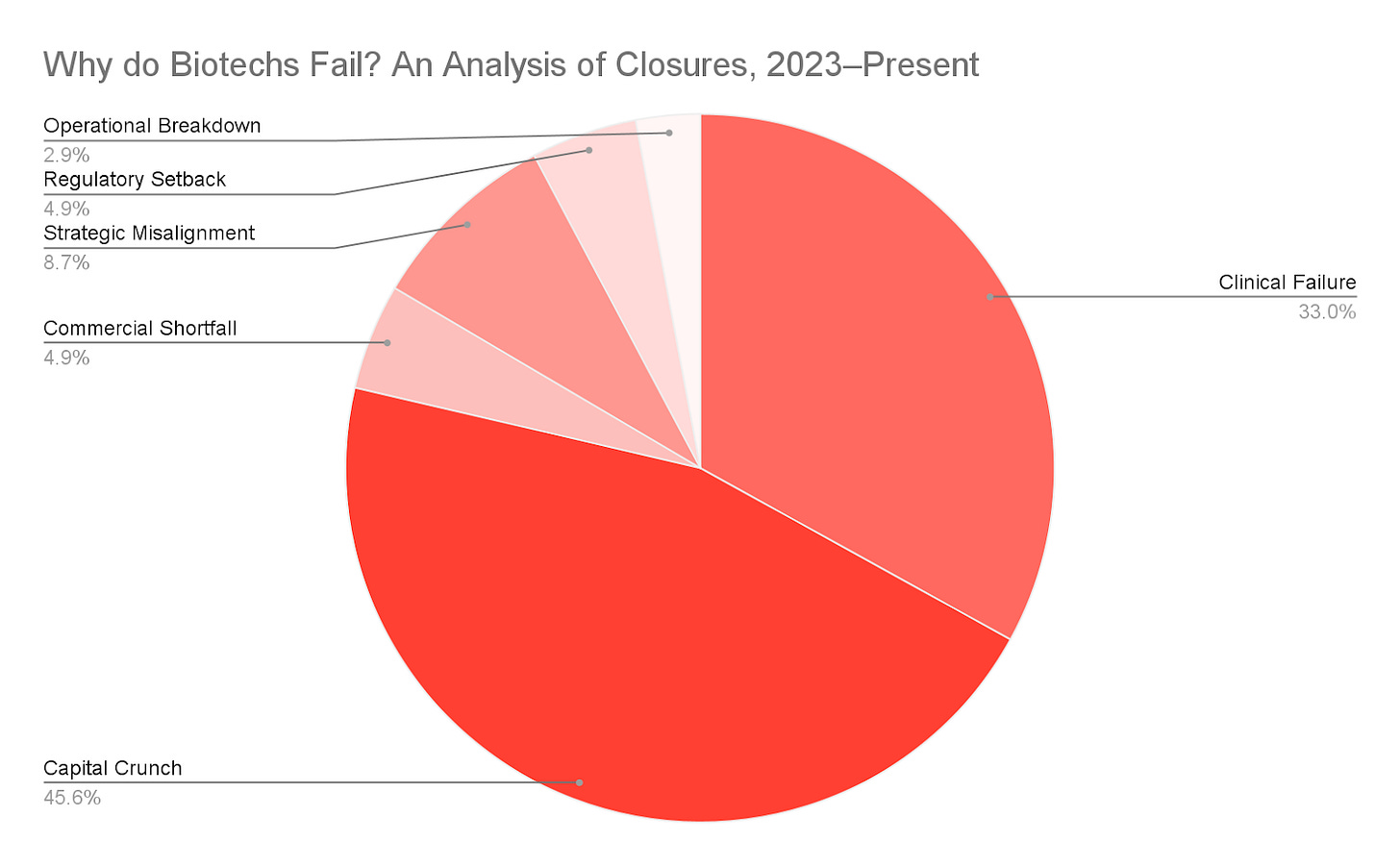

To better understand the drivers of biotech company closures, we conducted what we believe is the first systematic review of all publicly disclosed biotech shutdowns (sourced from Fierce Biotech and Biospace) between January 2023 and August 2025. We documented the stated reasons for failure in 64 companies and categorized each into one or more of six major clusters:

Capital Crunch: Companies in this category either exhausted cash runway too quickly (Excessive Burn Rate), were unable to secure additional financing to continue operations (Lack of Investor Confidence), or were caught in an extreme downturn (Macroeconomic Landscape).

Clinical Failure: In these cases, the company’s lead program(s) failed to meet primary endpoints or generated unacceptable safety signals in preclinical or clinical trials.

Strategic Misalignment: This category encompasses companies whose flawed or poorly timed strategic choices left them vulnerable. This includes over-reliance on a single asset or partner, costly failed mergers, overextension into too many programs, or the pursuit of markets misaligned with the company’s capabilities or resources.

Commercial Shortfall: Companies whose clinical-stage or approved asset failed to achieve market traction due to weak sales, crowded competitive pressure, insufficient differentiation, pricing/reimbursement barriers, or an overestimated market opportunity fall into this category.

Regulatory Setback: This category includes companies that faced adverse regulatory actions such as a clinical hold, complete response letter, refuse-to-file decision, or an unexpected data requirement that derailed the company’s path to market.

Operational Breakdown: This rarer category includes companies whose internal execution failures such as mismanaged trials, governance lapses, founding team indecision, or platform immaturity, accelerated failure. We predict this category is underrepresented in our analysis, skewing toward pre-seed/seed biotechs whose data was unavailable.

See the raw data here.

While clinical trial failures accounted for approximately one-third of public explanations for recent biotech closures, capital crunch remained the most significant factor, underscoring that financing risk, not science alone, is the dominant existential threat. A subgroup analysis revealed that of companies for whom capital crunch was a primary cause of failure, lack of investor confidence accounted for nearly three-fourths (72.5%) of cases, whereas excessive burn rate (19.6%) and macroeconomic landscape (7.8%) made up the minority. However, these three players are often interrelated, and thus cannot be considered in isolation—rapid cash burn can erode investor confidence, just as a poor funding climate can magnify the effects of either; thus, this subjective analysis cannot be taken for a definitive causal hierarchy of risk, but rather as a directional snapshot of publicly visible patterns.

Lastly, strategic errors, regulatory barriers, commercial blunders, and operational breakdowns together accounted for over 20% of publicly stated explanations for recent biotech failures. It is important to note, however, that the analysis above is limited to publicly disclosed information, and without access to internal decision-making processes, private financial data, and unpublished trial results, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about any given company’s demise. age1 looks forward to when a more rigorous, objective, and data-complete analysis can be conducted across the biotech sector to better inform founders, investors, and the public about the drivers of survival and failure in this industry.

In this series, we highlighted several unnerving stats about building in biotech. But don’t let us scare you away! By learning from the blunders above, and recognizing key patterns of failure, biotech founders have the opportunity to develop adaptable strategies to substantially increase survival odds.

age1’s Biotech Operator Checklist: Avoiding Common Pitfalls

I. Capital & Runway Planning

Have we explored all potential funding avenues (CPRIT, STTR, SBIR, ARPA-H, and other non-dilutive sources) alongside traditional investor capital?

When raising money, are we accounting for the expected, the unexpected, and planning long-term? On top of clinical trial costs, capital is necessary to fund CMC, commercial planning, and recovery from any obstacles along the way.

Can we sustain operations for ≥12 months without any additional cash infusion?

Does >30% of our future runway rely on payments from a single partner or counterparty?

Are we timing fundraising to valuation peaks around pivotal milestones, rather than waiting until runway is critically low?

II. Scientific & Clinical Rigor

Have third-party labs reproduced our core mechanistic readouts with blinded protocols? If not, is there sufficient genetic, epidemiological, preclinical, and mechanistic evidence to justify capital influx?

Have we thoroughly examined all safety and efficacy data to date on analogous drugs, reviewed historical literature, and conferred with independent KOLs to uncover blind spots?

Does our chosen indication clearly align with mechanism and manageable clinical endpoints? Are market size, payer burden, and mechanistic rationale aligned?

Are trial endpoints rigorously validated, clinically relevant, and powered adequately for symptom benefit—not just biomarkers?

III. Market & Portfolio Strategy

Is our pipeline breadth manageable for our capital and resources? While a multiasset portfolio is critical to risk management and financial success, spreading too thin can leave a company underfunded, understaffed, and incapable of reaching an inflection point.

Have we begun payor conversations ≥6 months pre-approval, with early onboarding of access teams? A 2022 McKinsey survey of first-time launchers revealed that successful companies onboarded a market access function team 4-6 months earlier than their less successful peers, 75% of which admitted that being late in the payor game was a costly choice.

IV. Operational Resilience

Has leadership conferred with enough third-party KOLs and mentors (clinicians, statisticians, CMC, ex-FDA) to identify blind spots and surface operational, regulatory, or clinical risks before committing significant capital or advancing into costly trials?

Is there a qualified backup for every critical supplier? As EY notes, today’s biotech manufacturing supply chain landscape remains uncertain, making this checklist item increasingly pertinent to today’s founders.

V. Risk & Crisis Management

Do we have a crisis-communications plan for bad data or safety events? Have we predefined quantitative criteria that would warrant shuttering trials before draining capital on a sinking ship?

Sources we liked:

Painful Truth: Successful Failure Of A Biotech Startup – LifeSciVC

The Intelligent Entrepreneur: Real and Illusory Margins of Safety in Company Building – LifeSciVC

Small but mighty: Priming biotech first-time launchers to compete with established players – McKinsey

Biotech Startups And The Hard Truth Of Innovation – Forbes

Good Science Doesn’t Guarantee Success: Why Some Biotech Startups Fail – BioSpace

So you want to start a biotech company – Sadhana Chitale, Colm Lawler, and Arthur Klausner

The Entrepreneur's Guide to a Biotech Startup, 4th Edition – Peter Kolchinsky

EY Biotech Beyond Borders Report 2025 – EY

We’d love to hear from our audience here as well: what questions would you recommend founders ask themselves before taking the next step?

This was a v informative read, thank you!