Betting on Biology: Part I

How to choose target that work, and succeed.

Choosing the right target is a prior probability problem. When only one in 200 protein-disease relationships is causal, preclinical target discovery operates at a false discovery rate of roughly 92.6%, which helps explain the observed ~96% overall drug development failure rate. The high attrition and wasted investment contributed to the case of Eroom’s law: the observation that the number of new drugs approved per billion dollars of R&D spend has halved roughly every nine years. Whether you are currently selecting a lead program or simply tracking the structural inefficiencies of drug discovery, these figures define your operating environment.

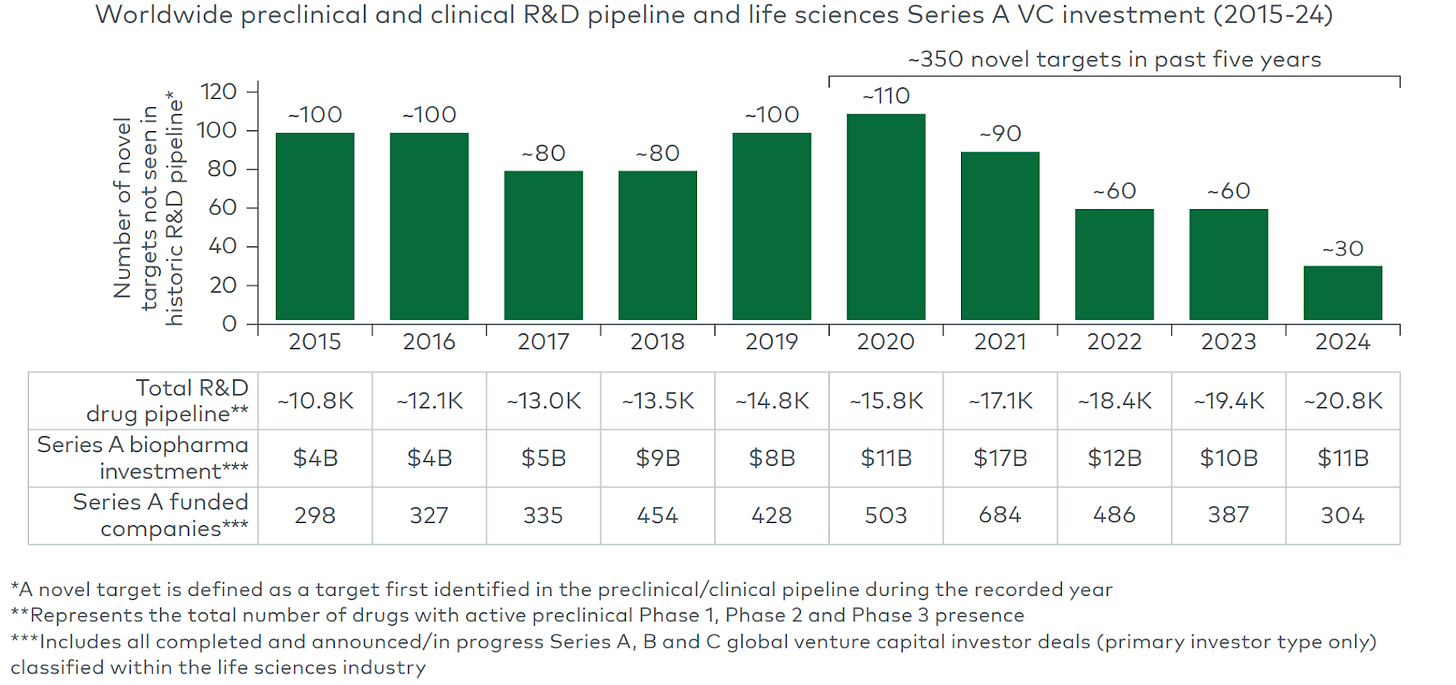

The industry’s fallback strategy today often is: take a validated target (with human or clinical evidence) and either improve convenience of the same modality or apply a new modality. That approach can yield quick gains but also crowding. For example, the PCSK9 gene (a cholesterol-regulating protease) was genetically implicated in cardiovascular risk: gain-of-function variants cause high LDL, while natural loss-of-function mutations give protection. Once PCSK9 was proven causal, dozens of companies rushed in: from first-generation monoclonal antibodies (evolocumab/alirocumab) to RNAi drugs, small molecules, vaccines, and now CRISPR-based gene editing. In one recent deal, Eli Lilly paid up to $1.3 billion for Verve Therapeutics’ one-time PCSK9 gene-editing program. This “validated target + improved/new modality” pattern yields value (the first PCSK9 drug lowered heart events), but it also means intense competition: the median number of approved drugs per target is only ~2, suggesting the lead drug captures most of the returns. Meanwhile, chasing untested new targets is intuitively the mirror risk. We see a widening pipeline gap in new targets, with novel target entry down threefold over the past decade despite unprecedented pipeline size and capital availability.

(Source: LEK report on novel targets)

We need better tools to navigate this landscape. By the end of the series, we want to create a clear and critical framework for identifying targets so that

We can distinguish real target information from model artifacts.

It provides a useful classification of target-origin stories along with a set of killer tests.

We understand better what are the compelling ways to discover molecular targets for age-related diseases today.

Definition and Scope of “Target”

We use “target” broadly. Consider these classes:

Single gene/protein

Proteases (PCSK9), kinases (mTOR), receptors (IL-6), enzymes (BACE1) targeted directly by small molecules/biologics

Pathway

NLRP3 inflammasome pathway etc.

Cellular state

Pathogenic cells (by Arda Tx), exhausted T-cells etc.

Circuit

Neural circuits (e.g. the basal ganglia loop), immune circuits (e.g. signals in tumor immunity) etc. → multi-target interventions / system-level perturbations.

Combo

Combine different classes of targets together.

*Less than 0.1% of all unique human target-indication pairings have advanced beyond preliminary testing stages in drug discovery. Vast swaths of biology are never tried because we can only prioritize a few targets at a time.

Typology of Target Identification

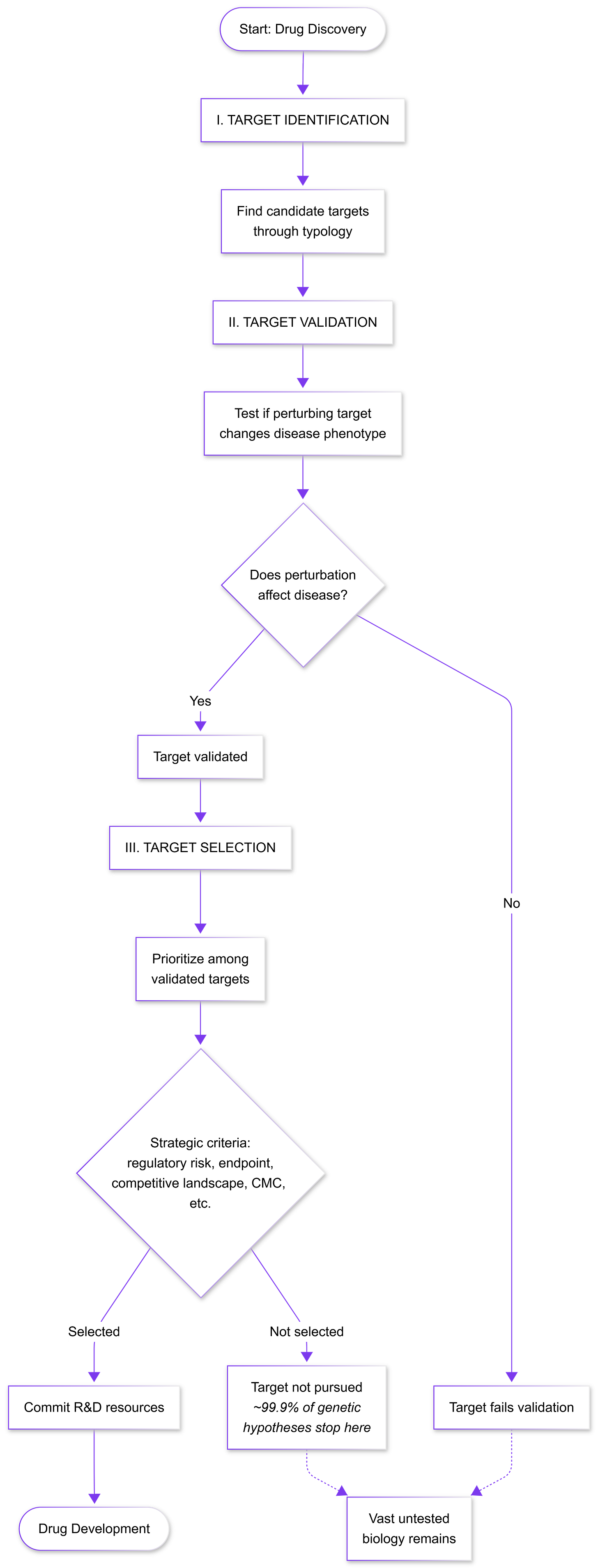

1. Pathway biology/mechanism-first targets

This classic strategy begins with a well-characterized physiological node (e.g. a hormone or pathway) and tests perturbing it in vivo. Its strength is obvious mechanistic coherence: if a gene or protein is known to regulate a key process (glucose, inflammation, etc.), targeting it feels logical. Decades of academic research reveals amylin as a pancreatic hormone co-secreted with insulin that regulates glucose homeostasis by inhibiting gastric emptying, inhibiting the release of the counter‐regulatory hormone glucagon and inducing meal‐ending satiety. The development of petrelintide leveraged its known mechanism.

Limitations of the approach

Correlation vs Causality: Signal ≠ cause

Novo Nordisk’s EVOKE/EVOKE+ trial results (November 2025) illustrate the risk associated with selecting targets through correlational pathway biology. GLP-1 receptor agonists appeared promising based on three evidence streams: 37% lower dementia incidence in diabetic patients receiving GLP-1 drugs versus other antidiabetics, preclinical neuroprotective effects, and mechanistic links between insulin resistance and neurodegeneration. Yet oral semaglutide failed to slow cognitive decline despite engaging AD-related biomarkers. This disconnect likely reflects that the observational correlation may stem from selection bias - healthier patients choosing GLP-1 therapy - rather than neuroprotection, and metabolic dysfunction may parallel rather than drive Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Pathway intersection does not equal causal involvement. However, interpretation requires caution as more results are revealed, and GLP-1 agonists may address contributory rather than primary pathology, potentially adding value in multifactorial treatment strategies even if insufficient alone.

Compensation

Compensatory mechanisms refer to adaptive responses within biological networks in which redundant or parallel pathways substitute for the inhibited target, preserving the disease phenotype. These mechanisms are especially common in signaling pathways that are highly interconnected, evolutionarily conserved, and involved in stress or inflammatory responses. In complex diseases, compensation can occur at the level of parallel kinases, such as the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathways substituting for inhibited p38; feedback loops increasing upstream signaling; and context-specific rewiring not captured in simplified models. The p38 MAPK pathway prompted inhibiting p38 as a treatment for arthritis, COPD, and autoimmune disease, with positive in vitro results. In vivo, parallel cascades compensate.

When compensatory mechanisms are likely, founders should prioritize upstream or less redundant targets, validate biology early in human systems, and design programs that anticipate network adaptation rather than single-node inhibition. In practice, this means using combination or polypharmacology strategies, stratifying by disease context and stage, and measuring beyond target engagement as an early go/no-go signal.

Wrong disease context

Targets validated in rodents or cell lines can fail in humans (“Translational Drift”), since models reproduce only fragments of disease biology. Conservation of genes is an inevitable consideration, in specific cases non-rodent animal models or “humanised” mouse models need to be employed.

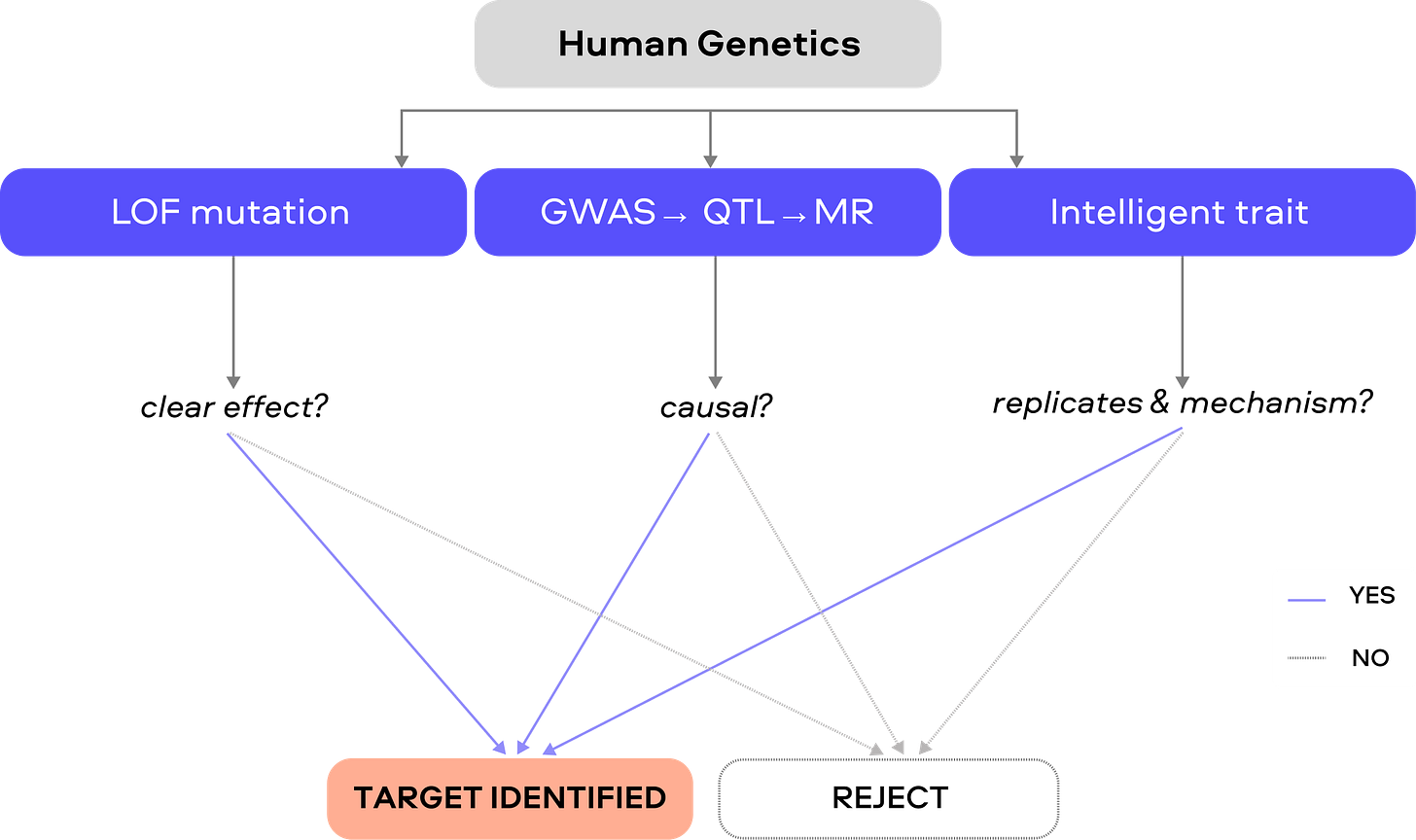

How to stress-test this typology?

We need to aggressively falsify them. First, test the target across multiple biological contexts: use different models (e.g. human cells or organoids as well as animals) and even non-disease settings to see if the intervention still affects the intended pathway. Show a clear dose-response between target perturbation and disease-relevant outcomes (e.g. pathology burden or functional improvement), not just surrogate markers. For example, rather than only measuring biomarker levels (like amyloid reduction), test cognition or survival. Second, employ genetic knockouts or CRISPR in human-derived cells/organs to confirm that loss of the target recapitulates the protective effect. A true causal node should produce a phenotype whenever it is perturbed. Third, if available, leverage human evidence: for instance, examine whether rare human knockouts or loss-of-function variants in the target gene have the predicted effect. This leads to our discussion of the second typology below on genetics.

*Push the target to fail by varying context, modality, and readout; only a driver that survives all falsification attempts is worthy of pursuit.

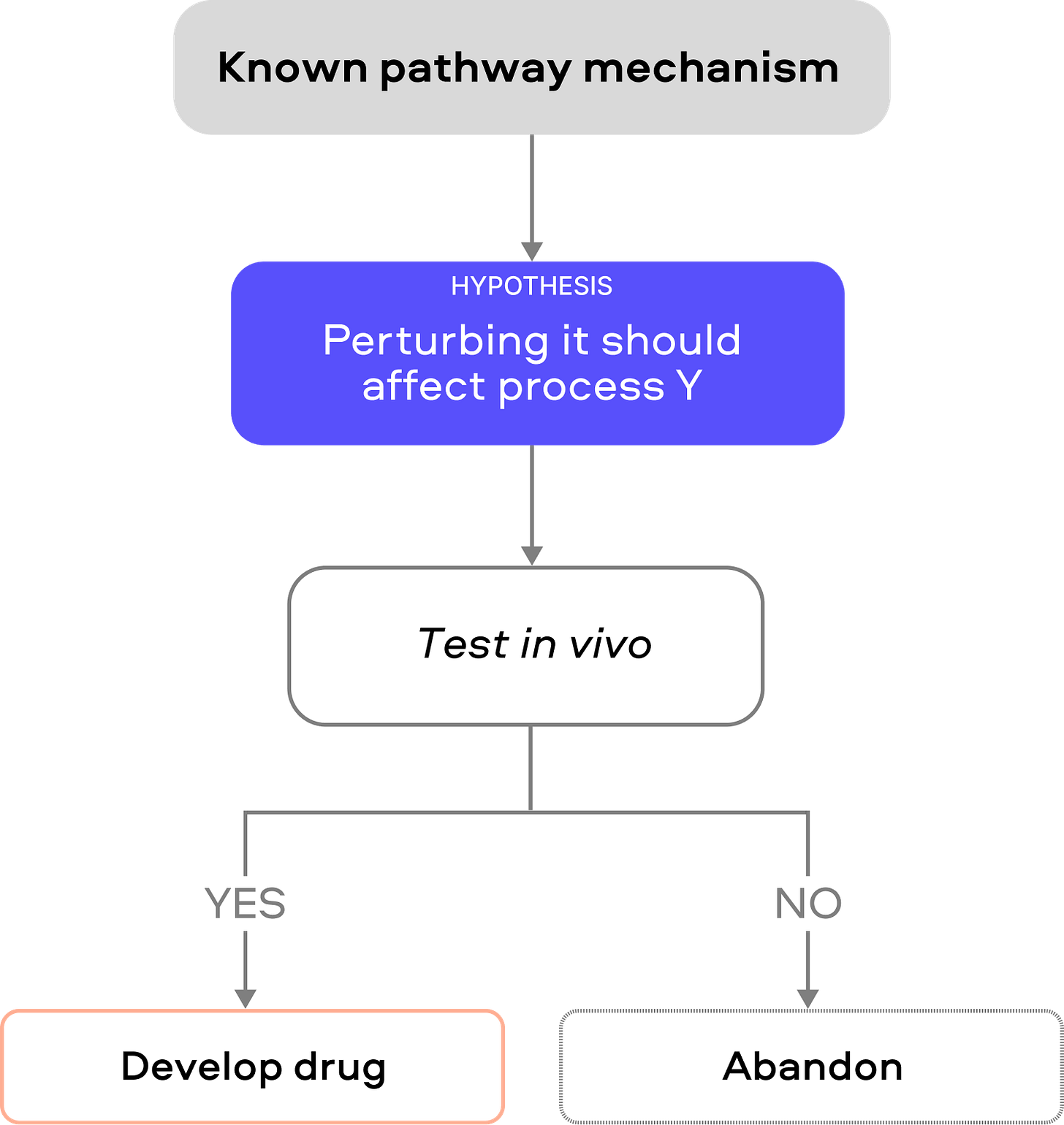

2. Human Genetic Causality

Human genetic evidence can identify causal targets in three broad ways:

Obvious traits / large-effect loss of function (LOF)

Some traits have rare “smoking-gun” mutations that cleanly shift biology. The poster child is PCSK9, similarly ANGPTL3 LOF carriers have much lower triglycerides/LDL (-27% and -9%) and lower atherosclerosis risk (-41%). The data supported the logic behind ANGPTL3 antibody evinacumab.

There are several limitations to this approach:

The biological context differs. Germline LOF represents lifelong, developmental perturbation across all tissues, whereas pharmacological inhibition occurs post-development in adults. A protein essential for early organ development may be safely targetable in mature tissues, or conversely, adaptive compensation during development may hide toxicities that appear with acute inhibition.

LOF genetics primarily inform disease prevention rather than progression or reversal. For continuous pathologies like atherosclerosis, where disease accumulates gradually, prevention and progression targets largely overlap. However, for diseases with distinct pre-disease and post-disease states, such as osteoarthritis, where cartilage deterioration crosses thresholds of chondrocyte loss and chronic inflammation, genetic protection from cartilage damage may not predict whether inhibiting the same target saves already-degraded joints.

Compared to obvious large-effect targets in European-ancestry populations already extensively mined, African, East Asian, Latin American, and other populations harbor distinct genetic architectures and may yet reveal high-value monogenic targets invisible in current datasets, particularly for diseases with variable prevalence or presentation across populations.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) / Mendelian randomization (MR) / Quantitative trait locus (QTL) methods

Genome-wide association studies first identify SNPs associated with disease, but establishing causality requires functional follow-up. QTL mapping links these variants to molecular traits (e.g. identifying SNPs as eQTLs or pQTLs affecting gene expression or protein levels). MR uses the genetic variant as an “exposure” to test if changing it causally impacts disease risk. Because alleles are randomly inherited, MR approximates a randomized trial and minimizes confounding. Bidirectional MR explicitly tests each direction (exposure→disease and disease→exposure) to validate causal direction. For drug-target validation, a cis‐MR approach uses SNPs near a candidate gene (e.g. affecting its protein) as instruments to directly test if that protein affects disease. GWAS/QTL mapping and MR analyses together build a causal chain from genotype to phenotype to disease.

This approach can inspire novel targets (e.g. bidirectional MR has highlighted INHBC in metabolic disease or FGF21 in kidney disease). Human genetic studies place INHBE (encoding the liver-secreted hepatokine Activin E) in the causal chain from GWAS to therapeutic target. Rare predicted loss-of-function (pLOF) variants in INHBE robustly associate with lower waist-to-hip ratio and less visceral fat. In vitro, an INHBE pLOF mutation causes ~90% reduction in secreted Activin E, effectively acting as a protein-level QTL and implying that attenuating INHBE signaling is beneficial. Carriers of INHBE pLOF have a favorable metabolic profile (lower triglycerides, higher HDL, lower glucose) and significantly less visceral adiposity than non-carriers, consistent with MR predictions of lower diabetes risk. This human genetics evidence effectively de-risked INHBE as an obesity target. Recently, in early clinical tests, INHBE silencing recapitulates the predicted effects: Arrowhead’s ARO-INHBE (with tirzepatide) achieved ~23% visceral fat reduction (versus ~7% for tirzepatide alone) and also raised lean mass ~3.6%, while Wave’s WVE-007 (single 240 mg dose) cut visceral fat ~9.4% and increased lean mass ~3.2%. These results closely align with the GWAS→QTL→MR→clinical framework for INHBE target validation.

The main failure modes here come from the limitations of genetic inference. Weak instruments (variants with tiny effect on the target) make estimates fragile or biased. Horizontal pleiotropy (a variant influencing multiple pathways) can be mistaken as causality and inflate false positives. Tissue-specificity also needs care: using a blood eQTL to infer a brain disease target can mislead. Effect sizes from discovery MR studies are often overestimated (the “winner’s curse”) and may shrink on replication.

“Intelligent traits”

Some methods refine traits to isolate mechanisms (e.g. waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for BMI to capture fat distribution independently of obesity, or defining “remnant cholesterol” to study triglyceride metabolism). In practice, an “intelligent” trait may generate associations that reflect statistical nuances rather than biology. To stress-test such leads, one should examine them in multiple populations and ensure they replicate outside the original cohort. Ideally, the engineered phenotype should map to the same gene or pathway in independent analyses and have a clear mechanistic rationale; otherwise, it may simply reflect model artifacts.

How to stress-test this typology?

To de-risk MR/QTL findings, one should assemble multiple independent genetic instruments (an allelic series) for the same target: if several distinct SNPs that each alter the gene/protein in graded ways all show consistent disease effects, confidence increases. One should also perform colocalization or multivariable MR with tissue-specific datasets (e.g. GTEx) to ensure the genetic signal aligns with the disease-relevant tissue to mitigate the “wrong tissue” risk. Wherever possible, orthogonal perturbation helps. Knock down or pharmacologically inhibit the candidate target in a human cell or animal model and check if the phenotype matches the genetic prediction. Finally, replicate the MR finding in larger independent cohorts to ensure the effect is not a statistical artifact. These steps help distinguish true causal targets from others.

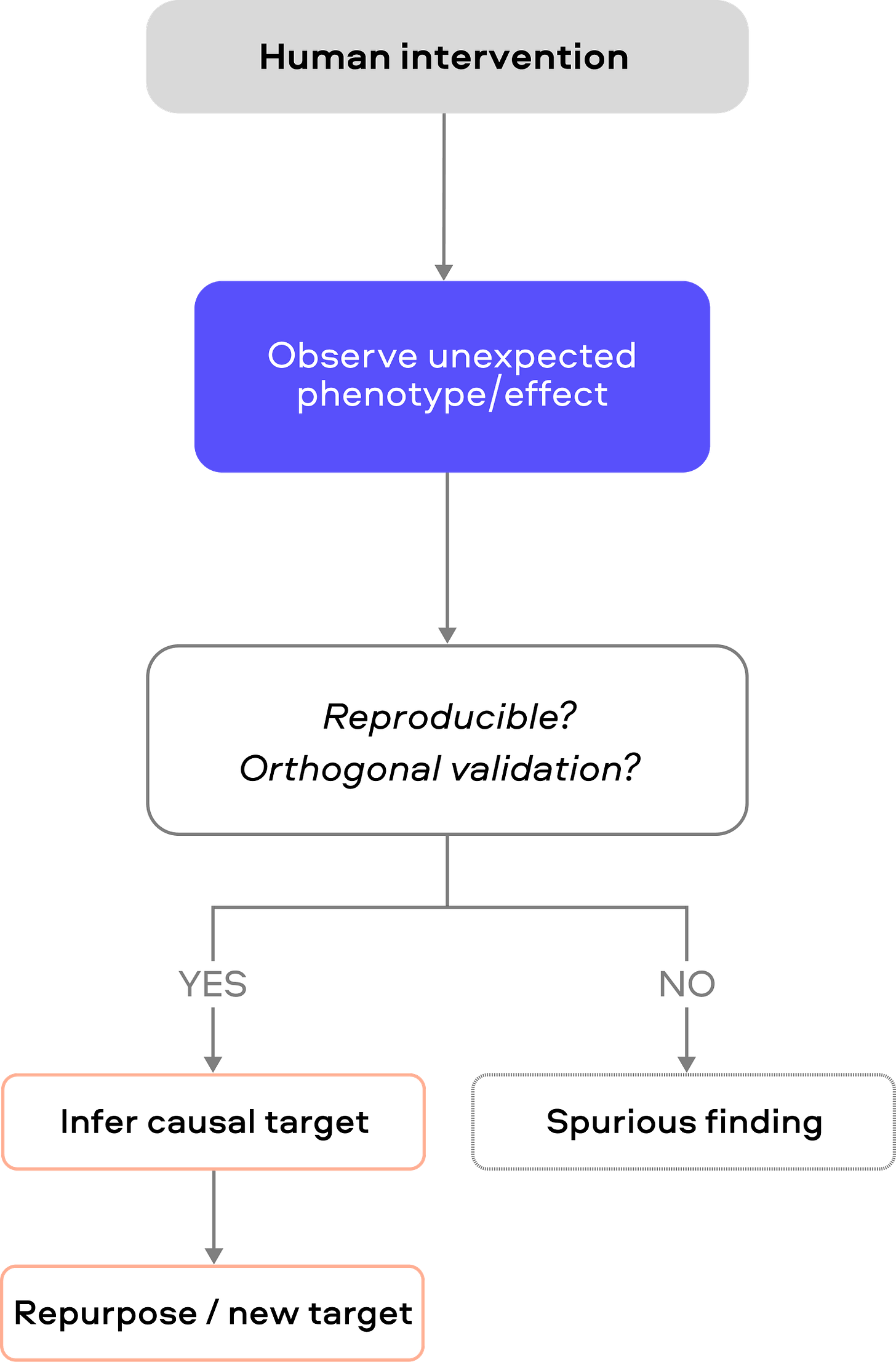

3. Human Perturbational Biology (Non-genetic)

While the last typology establishes whether a pathway is causally involved in disease, some of the most actionable biological insights in medicine have come from observing unexpected phenotypes following human intervention.This strategy uses natural and clinical “experiments” in humans (drug treatments, infections, surgeries, etc.) to infer targets. Famously, sildenafil (Viagra) was repurposed from treating angina to erectile dysfunction. Likewise, large observational studies have linked routine shingles (herpes zoster) vaccination to lower dementia risk. For example, a Welsh regression‑discontinuity analysis found that live zoster vaccination cut new dementia diagnoses by about 3.5 percentage points over 7 years (∼20% relative reduction). Additionally, from the CANTOS trial (an IL‑1β antibody for atherosclerosis), canakinumab reduced recurrent cardiovascular events as well as dramatically lowered lung cancer and total cancer mortality. These findings suggest that perturbing IL‑1β (an innate‐immune cytokine) conferred unexpected protection against smoking‑related cancer.

Limitations of the approach

Search space and retrospective constraints

The typology is largely retrospective; we are restricted to studying biological pathways that nature or medicine has already “intervened” upon. This creates a “streetlight effect” where we only look where the light is brightest. Vast areas of the genome or non-direct effects without clear genetic associations remain invisible to this typology, and because we rely on existing perturbations, identifying “first-in-class” targets that don’t have a natural human proxy is especially challenging.

Selection bias

Vaccinated, treated, or trial-enrolled populations differ systematically from controls (health-seeking behavior, comorbidities, access to care). Apparent benefits may partly reflect who gets treated rather than what was perturbed.

Effects may be specific to the population, disease stage, or exposure context.

Causal confounding

Determining the direction of a relationship is a primary hurdle when using EHR-linked frameworks or MR. The underlying disease (indication) often carries its own inherent risks that correlate with the outcome being measured. A drug may appear to cause an adverse event, but that event may actually be a symptom of the very disease the drug was meant to treat.

Mechanistic ambiguity and pleiotropy

Difficult to attribute observed phenotypes to a specific target rather than off-target or downstream immune effects.

How to stress-test this pathology?

Orthogonal validation is important. If a candidate pathway emerges from a drug study, test whether other drugs or interventions expected to act on the same pathway produce consistent molecular changes. For example, if two unrelated anti-diabetic agents both reduce a particular inflammatory marker, that strengthens the link. Otherwise, if a signature is unique to a single drug, it may be an off-target effect. Within individuals, longitudinal designs (multiple timepoints) help separate direct drug effects from temporal noise. Finally, use orthogonal readouts (biochemical assays, imaging, functional tests) rather than relying solely on high-throughput omics. A purported target should correlate with improvements in hard endpoints across perturbations, not just with a surrogate biomarker. To increase the efficiency of screening, we see recent efforts in perturbing biology deliberately in scale.

This is the first of a five-part series. Next week, we’ll publish an in-depth analysis of perturbation-based target discovery, dissecting how to separate signals from noise when scale meets biology. Stay tuned!

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to Satvik Dasariraju for the inspiration, thoughtful comments, and prompt answers to my many questions; to Alex Colville for invaluable writing guidance throughout the process; and to all dedicated age1 crew for helpful pointers. Cheers!

What a strong, high-signal framing: target selection as a prior probability problem, not a vibes-based narrative. The way you connect (i) “only ~1 in 200 protein–disease relationships is causal,” (ii) the implied ~92.6% false discovery rate in preclinical target discovery, and (iii) the downstream ~96% attrition in drug development makes the core point impossible to ignore: most programs aren’t “badly executed,” they’re born with low base rates.

I also appreciated the nuance around the industry’s default playbook (“validated target + new/improved modality”). It does generate patient benefit (PCSK9 is the canonical case), but your observation about crowding, where the lead asset captures most of the returns, helps explain why “safer” strategies can still be economically and scientifically brittle.

As a physician-scientist, the most actionable piece is your insistence on aggressive falsification and context-stress testing (human systems, dose–response tied to meaningful endpoints, genetics where available, and a clear plan for compensation/rewiring). That’s exactly the mindset shift we need if we want more first-in-class mechanisms, especially in aging biology, where pathways are intertwined and “target engagement” can be a seductive mirage.

Fantastic work! Love the comprehensive overview and thoughtful guidance. So many things need to come together to develop a drug for a novel target. It’s incredible the amount of effort and testing required. And then there’s always serendipity - making the right connection with patients, researchers, investors. Many external factors that also influence what gets developed and what doesn’t.