How Scalable Perturbation Sequencing Rewrites Causal Target Discovery

From tracking cell survival to programming functional identity through billion-cell atlases

Perturbation at Scale

In biology, a perturbation is any intentional change made to a cell, like turning a gene off, overexpressing a protein, or adding a drug. Perturbation at scale is the transition from doing this to one gene at a time to doing it to every gene in the genome simultaneously. By using tools such as CRISPR to knock down thousands of genes across millions of individual cells and then sequencing the results, we create a high-resolution data point for every possible intervention. We can test every possibility at once, quickly assess causal hypotheses and rule out what doesn’t work. A useful perturbation dataset should be evaluated via:

Breadth: Genome-wide or near-genome-wide perturbation coverage

Depth: High-content readouts (single-cell transcriptomics, epigenomics, spatial or functional phenotypes)

Context: Perturbations resolved across cell types, states, and increasingly, combinatorial or “combo” modalities

On January 20, 2026, Parse Biosciences and Graph Therapeutics announced a partnership to construct a large-scale functional immune perturbation atlas, combining pooled genetic perturbations with single-cell readouts across immune states. Just days earlier, the Norman lab reported the largest exhaustive genetic interaction map ever built in human cells: 665,856 pairwise perturbations across 46 million clonal lineages, and critically, the first map at this scale using measurable traits other than whether a cell lives or grows. Adding to this momentum, Illumina introduced the “Billion Cell Atlas“ on January 13, a genome-wide dataset designed to capture how one billion individual cells respond to CRISPR-driven genetic changes in 200+ cell lines.These datasets are transformative because they shift the focus from cell survival to cell state, a cell’s functional identity. After getting single-cell sequencing of a perturbed cell, you gain two major useful capabilities:

Navigation: We can treat cell identity as a position on a map. This allows us to identify exactly which interventions shift a cell from a “diseased” toward a “healthy” reference state, or towards a different identity, assuming that a priori healthy vs. old cells from primary samples have been collected.

Prediction: Because these maps capture millions of interactions simultaneously, they serve as a predictive model of the cell’s internal logic in the long run. This “searchable index” holds complex biological information that is far too non-linear and emergent to be derived using traditional math or differential equations.

The idea itself is not new. The 1979-1980 Heidelberg screens in Drosophila pioneered systematic mutagenesis, then in the 1980s, High-throughput screening (HTS) industrialized chemical perturbation in pharma, scaled up from 800 compounds per week in 1986 to 7,200 per week by 1989 in Pfizer. Genome-wide RNAi libraries followed in the 2000s, and CRISPR-Cas9 screens in the 2010s expanded the search space further, yielding bona fide clinical targets. Research utilizing the GeCKO (Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout) library successfully identified CUL3 (Cullin 3) as a high-ranking candidate gene whose loss gives resistance to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in melanoma models. By perturbing gene function at the DNA level, researchers demonstrated that the complete loss of CUL3 function significantly alters cellular responses to targeted therapies. These findings illuminate the importance of the neddylation pathway, which is required for the activation of Cullin proteins like CUL3, and provides a genetic rationale for investigating therapeutic inhibitors like pevonedistat that target this specific regulatory mechanism. In parallel, the Connectivity Map (Broad Institute, 2006) demonstrated that cell states themselves could be profiled and indexed at scale.

What is different now is not just throughput, but dimensionality. We have crossed a phase boundary: from perturbation as a sparse experiment to perturbation as a high-resolution map of causal biology. This shift reframes the core bottleneck in drug discovery. The problem is no longer a shortage of targets, rather a shortage of high-dimensional understanding of those targets. What does this gene do in a human cell? In a diseased tissue? Under aging, stress, or immune activation? Will modulating it repair the system, or trigger compensatory failure?

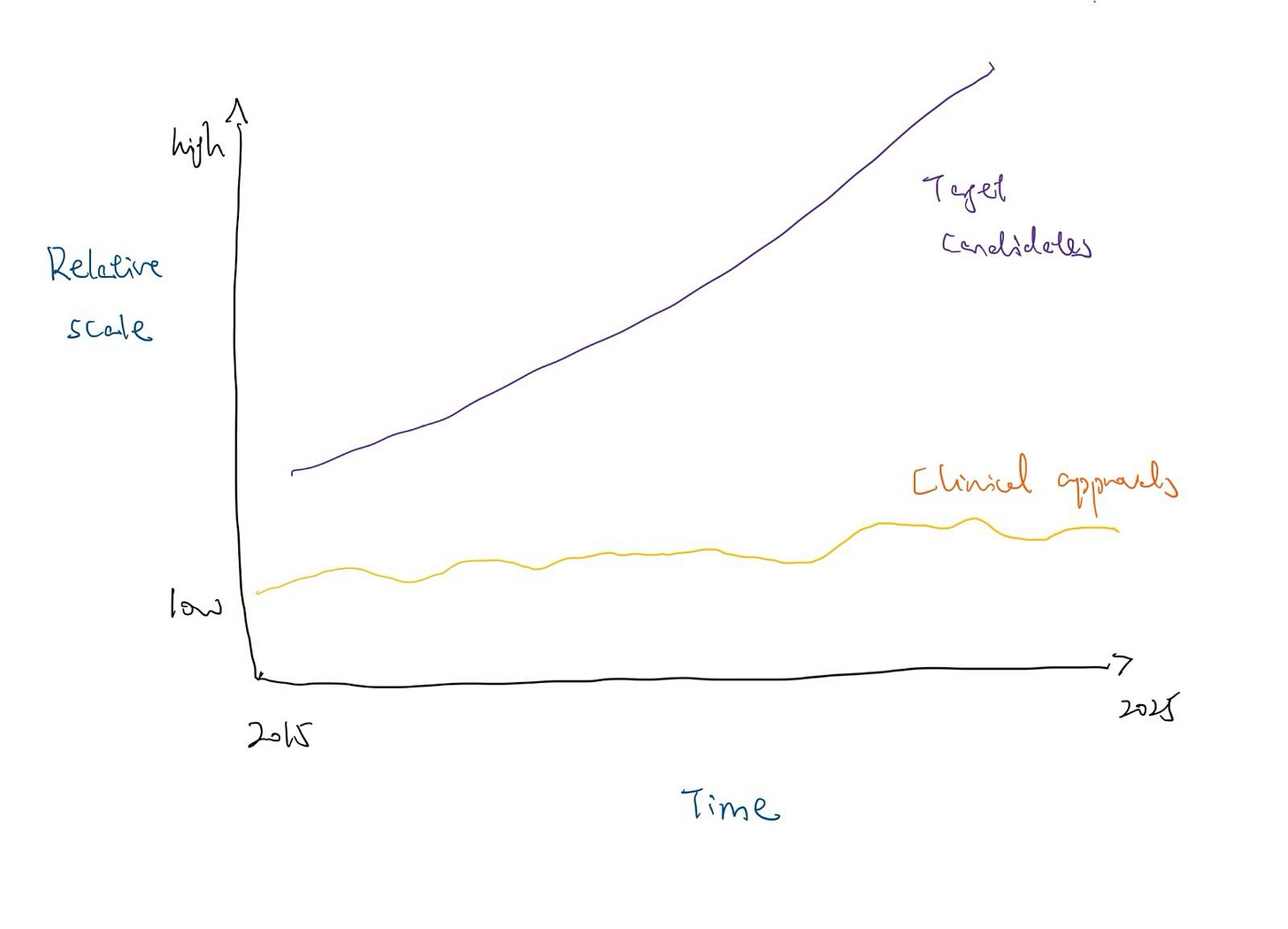

Modern automated platforms can now identify potential drug targets 10,000 times faster than traditional methods. Additionally, the “evidence base” for target-disease associations has exploded. Since 2015, the accumulation of supportive biomedical data driven by GWAS, CRISPR screens, and single-cell “omics” has reached a scale where nearly 30 million pieces of evidence now exist in open platforms. Despite this massive influx of candidates, the rate of FDA approvals has not followed suit, with approvals for New Molecular Entities largely fluctuated between 35 and 55 annually for the past decade.

[*Conceptual graphic]

What remains scarce, and increasingly decisive, is the ability to interpret perturbations, extract causal structure from high-dimensional data, and select the right lead from an overwhelming search space.

This essay argues that perturbation at scale is not just a faster way to find targets. It is a fundamental reorganization of how we learn biology, and a necessary response to the widening gap between experimental capacity and causal understanding.

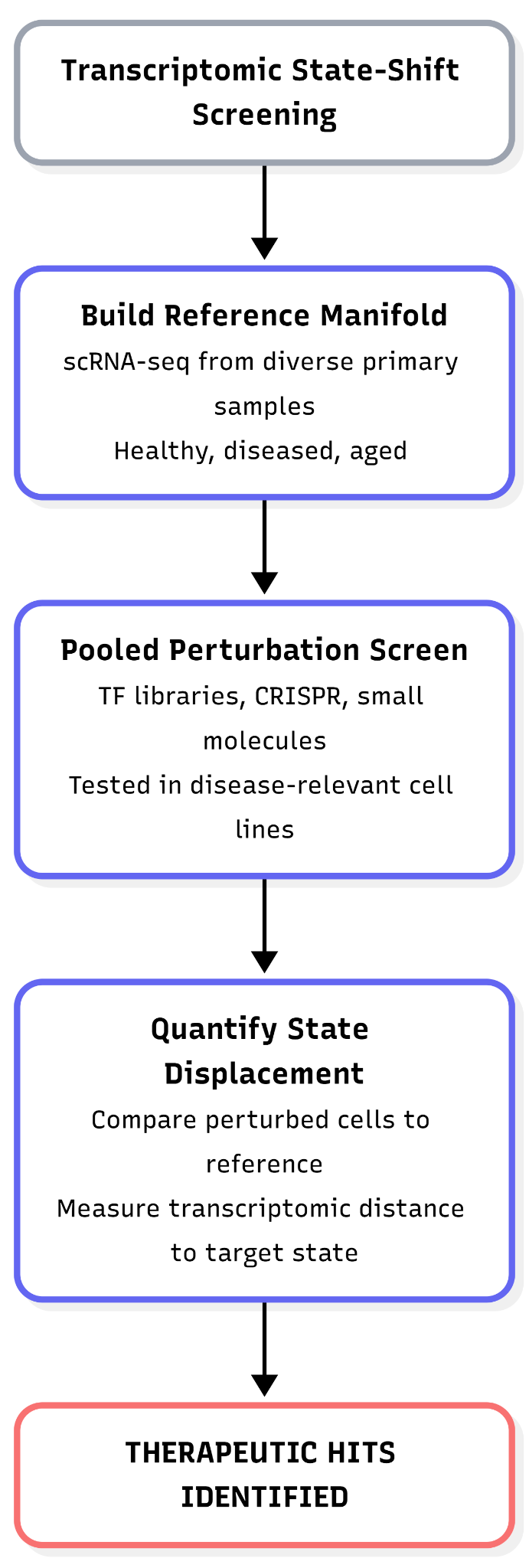

1. Transcriptomic state-shift screens

Transcriptomic state-shift screening uses large-scale gene expression measurements to identify perturbations that move cells from an undesired biological state toward a predefined target state. The core idea is to treat cell identity as a position in a transcriptomic state space: a low-dimensional manifold learned from gene expression data, such as an axis spanning “aged” to “youthful” or diseased to healthy cellular programs.

In practice, researchers first construct a reference manifold of cellular states using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Because human aging and disease are driven by diverse epigenetic codes across various genetic backgrounds, this requires collecting primary tissue samples from a broad range of healthy, diseased, and aged individuals. It is necessary to capture real biological variation rather than literature-based assumptions from immortalized cell lines, and ensure the resulting models are grounded in human biology. To maintain a clear signal, the cell type must be held constant across these samples. Thousands of candidate perturbations, such as pooled transcription-factor overexpression libraries, CRISPRa/CRISPRi guides, or small molecules, are then introduced in parallel. However, these exhaustive screens are typically not performed on the original primary donor samples, they are carried out instead in more scalable, ‘accessible’ systems like a curated set of disease-relevant cell lines. Primary cells are generally too scarce, fragile, and short-lived to survive the massive throughput required to test millions of combinations. Each cell’s transcriptome and perturbation identity are jointly captured, typically via pooled single-cell readouts.

By comparing the perturbed cells to our healthy reference, we can see exactly which interventions push a diseased cell back towards a healthy state. The effect of a perturbation is quantified using metrics such as transcriptomic distance, state displacement, or a model-derived aging score.

For example, NewLimit’s pooled reprogramming screens evaluate whether specific transcription-factor combinations shift aged cells toward a youthful transcriptomic profile. Hits are perturbations that reproducibly and significantly reduce inferred transcriptomic age or induce the target gene expression.

Transcriptomic state-shift screens provide an information-dense readout of perturbation effects. Single-cell resolution resolves heterogeneous cellular responses and avoids false negatives caused by bulk averaging, while enabling thousands of perturbations to be assayed in a single pooled experiment, with each cell effectively serving as an independent test.

As a result, these screens scale efficiently to very large perturbation spaces. For example, NewLimit reports pooled evaluation of >4,000 transcription-factor combinations within a single experimental framework. The resulting high-dimensional expression profiles can be quantitatively analyzed using statistical or machine-learning models to rank perturbations by the magnitude and consistency of their induced state shift.

Crucially, transcriptome-based hits can uncover previously unappreciated biology. Rather than relying on proxy phenotypes or viability effects, the approach directly measures whether perturbing a given target drives cells toward a particular molecular state, establishing a causal link between target modulation and the desired transcriptomic outcome. This strategy allows researchers to go beyond the inherent limitations of human genetics, which is fundamentally filtered by natural selection. Traditional genomic studies are powerful, but they are restricted to variants that have successfully persisted through evolution. Many of the most powerful biological levers remain undiscovered because they are tied to evolutionary constraints or developmental necessities. For example, a mutation that could theoretically reverse an adult disease state might never be observed in human populations because it would be embryonic lethal during early development. Furthermore, evolution does not “trace” every possible genetic combination, which leaves vast regions of the biological landscape unexplored.

Limitations of the approach

Transcriptome ≠ function

Changes in gene expression profiles do not always translate to improved cellular or organismal function. An intervention may make a cell’s transcriptomic signature resemble a desired state (e.g. a “younger” or less diseased profile) without fixing underlying functional deficits. In aging research, many treatments targeting single molecular hallmarks altered gene expression but failed to increase lifespan or restore health in vivo.

Similarly, in immune modulation, simply reversing exhaustion-associated transcripts in T cells is not guaranteed to restore their antitumor function. It remains challenging to assess whether altered exhaustion markers truly correlate with durable functional recovery.

Undesired coupling of state changes

The desired state shift can be coupled to unwanted cellular changes. A prominent example is partial cellular reprogramming to reverse aging: while short-term OSKM factor expression can reset epigenetic age and gene expression, it also pushes cells toward a pluripotent-like state. This dedifferentiation erodes cell identity and can lead to uncontrolled proliferation.

In vitro hits vs. in vivo efficacy

Transcriptome-based screens often identify perturbations that look promising in cultured cells but falter in living organisms. One reason is that complex physiological contexts are not captured in vitro, cell-line gene expression responses may not replicate in tissues or patients. Notably, despite the excitement around reprogramming factors and chemical cocktails that reverse cellular age in vitro, only a single peer-reviewed study from Rejuvenate Bio thus far has shown a significant lifespan extension in normal adult animals using these methods.

Logistical constraints

High-resolution mapping currently relies on specific physical requirements. First, we need high-quality “reference” cells; while we can biopsy living tissue, collecting from autopsies is difficult because cell states begin to degrade immediately after death. Second, once we identify a gene that can shift a cell state, we must be able to actually reach that cell in a patient. This limits the current impact of these screens to cell types where we already have reliable ways to deliver a drug, like those in the blood, liver, or eye.

How to stress-test this approach?

Transcriptomic hits require rigorous downstream validation to confirm that molecular changes translate into genuine functional benefits. Key tests include:

(1) Functional Assays: Does perturbation actually make old or diseased cells act young or healthy? For example, a hit from a gene expression screen should be tested in a functional readout like regenerative capacity, stress resistance, or a disease-specific behavior. NewLimit followed this principle by taking a top TF hit into animal models - formulating it as an LNP-mRNA therapy and showing it restored liver regeneration in old mice. Such an in vivo rescue of function is the ultimate proof that the transcriptomic shift was meaningful.

(2) Orthogonal Markers: Check other layers of biology, e.g., does the intervention also reduce epigenetic age or improve protein-level biomarkers? Consistency across orthogonal “youth” metrics builds confidence that the target has true causal power.

(3) Specificity Checks: Ensure the perturbation isn’t causing broad stress or proliferation that masquerades as a rejuvenation signature. This can be done by measuring whether cell-type identity markers remain intact (no unwanted lineage changes), and by looking for adverse transcriptional programs (p53 activation, inflammation) in the single-cell data.

(4) Time-course durability: A durable effect is more likely to be therapeutically relevant so evaluate if the desired expression changes persist after the perturbation is withdrawn.

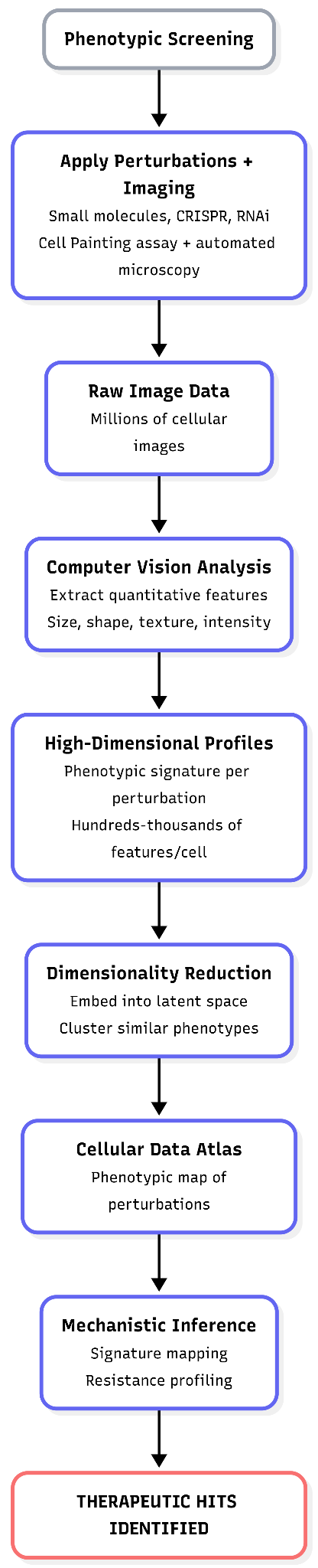

2. Phenotypic screens

Phenotypic screening interrogates biological targets indirectly by measuring high-level cellular outcomes (phenotypes) rather than directly assaying a specific molecular species (e.g., a protein’s enzymatic activity or a transcript’s abundance). A phenotype here refers to observable cellular properties such as morphology, organelle organization, growth, survival, or reporter activity.

In practice, phenotypic screening often relies on automated, high-content assays that can capture many features simultaneously across thousands to millions of perturbations. A canonical example is the platform developed by Recursion, which makes extensive use of the Cell Painting assay. In this approach, cells are exposed to perturbagens, such as small molecules, CRISPR-based gene knockouts, or RNA interference, then stained with a standardized set of fluorescent dyes that label major cellular compartments. Cells are imaged at scale using automated microscopy.

Computer vision and machine-learning models extract hundreds to thousands of quantitative features per cell, describing aspects of size, shape, texture, intensity, and spatial organization. The result is a high-dimensional phenotypic signature for each perturbation.

These high-dimensional phenotypic profiles are typically embedded into a lower-dimensional latent space using dimensionality-reduction or representation-learning methods. Perturbations that induce similar cellular changes cluster together in this space. At Recursion, this strategy has been applied to build a large-scale cellular “data atlas” comprising hundreds of millions of images across dozens of human cell types, spanning both genetic perturbations (e.g., gene knockouts) and chemical treatments.

Mining such an atlas enables mechanistic inference by similarity. For example, if an uncharacterized compound induces a phenotype that clusters with the knockout of a gene from a known pathway, this suggests that the compound may act on that pathway or on a molecular target upstream or downstream of it. Importantly, this inference is probabilistic: phenotypic similarity constrains the space of plausible mechanisms but does not, on its own, prove direct target engagement.

Not all phenotypic screens rely on rich imaging. Some focus on more targeted functional readouts, such as cell viability, proliferation rate, or reporter-gene expression under defined conditions (e.g., metabolic stress, drug resistance, or inflammatory signaling). These assays still qualify as phenotypic because they measure an integrated cellular response rather than a single molecular interaction.

A common strategy for deconvolving phenotypic hits (i.e., linking an observed phenotype to an underlying mechanism) is signature mapping. In this approach, the phenotype of a hit (whether an image-based fingerprint or a gene-expression profile) is compared against a reference library of signatures derived from perturbations with known targets or mechanisms. The original Connectivity Map applied this concept to transcriptional profiles; analogous logic is now widely used with imaging-based phenotypic data.

Another powerful deconvolution method is resistance profiling. When a small molecule produces a strong phenotypic effect but its target is unknown, researchers can perform a secondary genetic screen (often using a genome-wide CRISPR knockout library) to identify genes whose loss suppresses or abrogates the compound’s effect. Genes that confer resistance are frequently directly explained by, or functionally connected to, the compound’s mechanism of action.

Conceptually, phenotypic screening asks: does any perturbation make cells look or behave more normally under a given condition? Mechanistic insight is then obtained not from the primary screen itself, but from downstream pattern recognition, comparative signature analysis, and targeted secondary experiments.

Phenotypic screening is most effective when the biological objective is already proven, but the chemical path to reach it is unknown. The development of risdiplam (for Spinal Muscular Atrophy) follows this logic. Before risdiplam, nusinersen (an ASO) and zolgensma (a gene therapy) had proved the “objective function.” They showed that increasing SMN protein levels in patients significantly improved motor function. While successful, they required complex delivery: nusinersen requires lifelong, repeated injections into the spinal fluid (intrathecal), and zolgensma is a one-time viral gene replacement delivered via IV. The industry wanted a small molecule (a pill) that could be taken at home and distributed systemically. The problem was, The SMN protein itself lacks a traditional “pocket” for a small molecule to bind to, making it a difficult target for conventional drug design. Instead of trying to engineer a stabilizer for an “undruggable” protein, researchers used a phenotypic screen to find a small molecule that could achieve the same outcome as nusinersen: correcting SMN2 splicing. They set the objective to match the success of the previous therapies and let the screen find the lever.

High-content imaging in particular captures an integrative picture of cell state: subtle changes in organelle shape, texture, or cell size can reflect pathway perturbations that genomic assays might miss. Modern machine learning (ML) allows extraction of these subtle phenotypes and clustering of related perturbations far beyond human visual ability. Another strength is scalability: platforms like Recursion’s can test millions of perturbation-condition combinations and profile each with thousands of features. This yields an extensive phenotypic map that can be mined repeatedly (a “searchable” index of biology). Also, phenotypic hits are directly linked to functional outcomes by definition, e.g., a compound that restores a diseased cell morphology or survival has already passed a kind of functional test in vitro. This tends to prioritize biologically relevant effects.

When combined with reference perturbations, phenotypic assays can also suggest mechanisms: Recursion demonstrated that morphologically similar knockouts often belong to the same pathway or complex (e.g., knocking out JAK1, STAT3, and other IL-6 signaling components all produced closely related phenotypic signatures). Thus, phenotypic screening can both identify and begin to mechanistically annotate novel targets.

Limitations of the approach

Ambiguity

Visual or functional phenotypes are often not specific. Many mechanistically distinct treatments cause overlapping phenotypic changes. For example, any severe stress or toxic insult may make cells round up or detach, a phenotype that doesn’t pinpoint a unique target. Such “mechanistic ambiguity” means the same cellular outcome (e.g. apoptosis, cell arrest) could result from very different molecular triggers.

Large-scale cell imaging often catches false signals from dust, lint, or blurry focus. Some chemicals also glow or dim on their own, making them look like a “hit” when they aren’t. Also, dead cells can trick the computer because of their morphological changes.

Cell type/model specificity

A phenotype observed in a particular cell line (often aneuploid cancer cells or immortalized lines) may not translate to primary cells or in vivo tissue.

ML models in cell testing can be tricked by hidden patterns, like which batch a sample came from or where it sat on a tray. If these aren’t managed, the computer learns to group samples by these accidental setup differences instead of their actual biological changes.

Phenotypic profiles can cluster compounds with similar action, they do not automatically reveal the molecular target. This is the flip side of not starting from a hypothesis.

“Common pathways”

Phenotypic screening can yield hits acting on known pathways like generic stress response that might alleviate multiple cellular problems transiently without truly addressing disease drivers.

Certain mechanisms recur across phenotypic screens because they universally perturb cells. For example, HDAC inhibitors, bromodomain (BRD4) inhibitors, mTOR pathway inhibitors, tubulin disruptors, and mitochondrial poisons are famous for appearing as hits in many phenotypic assays. Modulating these targets produces strong phenotypes (changes in gene expression, cell cycle arrest, cell death, etc.) in a wide range of contexts.

How to stress-test this approach?

(1) Reproducibility and specificity: Re-test the hit in the same assay across independent experiments and controls. Does the phenotype consistently reproduce? Does the intervention only correct the intended phenotype or does it also cause other aberrations? For example, if a small molecule normalizes cell morphology, one would verify it doesn’t also, say, trigger massive cell death or stress pathways as side-effects (using additional stains or assays).

(2) Mechanism deconvolution: Apply signature mapping or resistance profiling to nail down the target. If the hit is a compound, perform a genome-wide CRISPR resistance screen: if cells lacking protein X become immune to the drug’s effect, that strongly implicates X as the target or pathway node. Conversely, if no clear resistance emerges or if multiple unrelated genes confer resistance, the mechanism may be off-target or poly-target. Another approach is proteomic pull-down (for compounds) to see what the molecule binds. For an image-based signature, check if it clusters with any known reference perturbation in the atlas – that can generate a hypothesis (“this looks like a TNF-alpha inhibition signature”) which can be tested by directly measuring pathway readouts or using known inhibitors.

(3) Orthogonal phenotypes: Validate the hit in a different assay that measures the core desired function. For instance, if the primary screen was based on morphology, test whether the hit also improves a relevant functional metric (e.g., contractility in a cardiac fibrosis model, or survival in a toxicity model). Recursion’s philosophy of “patient connectivity” is relevant here – they seek evidence that perturbing the target maps onto real disease biology. This could mean testing the hit in patient-derived cells or organoids to see if it reproduces the beneficial effect.

(4) In Vivo efficacy: Ultimately, a “killer” validation is demonstrating the hit’s effect in an animal model. If a compound arises from a phenotypic screen, one would administer it in a disease model and look for phenotypic improvement (tumor shrinkage, improved tissue function, etc.). Phenotypic hits can be less validated on mechanism, but more directly validated on outcome: if it works in vivo, that validates the approach, even if the target is unknown – though target ID will still be needed for optimization.

(5) Counter-screening for off-targets: Ensure the hit is not acting through known undesirable mechanisms. For example, one might counter-screen the compound in a panel of assays for common toxic liabilities (hERG channel, etc.) or check if the phenotypic change is simply due to cell cycle arrest or apoptosis (common artifacts). In summary, the path from a phenotypic screen to a real target demands connecting the phenotypic outcome back to a molecular cause and confirming that cause actually drives disease reversal in vivo. Only through such multi-pronged validation can one be confident that a phenotypic screening hit represents a viable, novel target (and not a dead-end artifact).

This is the second piece in the “Betting on Biology” series. Next week, we explore two distinct strategies for anchoring drug discovery in real-world biology: first, using human primary tissue perturbation platforms to test how interventions behave in the complex, 3D environment of fresh patient samples directly; and second, leveraging comparative biology to identify novel targets by studying how different species have evolved unique ways to resist disease. See you soon.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to Satvik Dasariraju for the inspiration, thoughtful comments, and prompt answers to my many questions; to Alex Colville for invaluable writing guidance throughout the process; to every age1 crew for helpful pointers; and to many amazing builders whose innovation and passion shaped the thesis of this piece. Cheers!