Anatomy of a Biotech Failure: Part I

Eight Case Studies in Shutdown History

In 2017, Bruce Booth at Atlas Ventures admirably published what he called an "investor's eulogy" in Forbes, detailing the rise and fall of Quartet Therapeutics, a seven-person Cambridge-based biotech developing BH4-targeting neuropathic pain therapeutics. Booth's case study is just one of many attempts by analysts and science writers to understand why once-promising biotech companies are so often gutted despite their seemingly straightforward science and well-qualified teams. Clinical failure is just one piece of the story; a growing body of evidence and post-mortems on biotech ventures indicate that operational blunders often play a more decisive role in a startup's collapse than science alone. In analyzing several companies for this piece, recurring archetypes stood out: safety-signal blindness, single lifeline dependency, market misfit, asset class myopia, and more.

In this article, age1 profiles (autopsies?) eight selected biotechs as case studies in the scientific, managerial, and operational missteps that can sink an early-stage company. We selected companies that garnered considerable attention in the biotech community at the time of their failure, and whose failures could be attributed to specific reasons that we believe, if detailed here, could offer valuable lessons to aspiring founders hoping to beat the odds.

It's important to note that this article only focuses on higher-profile biotech failures—companies whose rise and fall left enough of a paper trail for post-mortem analysis. In the last decade, there have likely been thousands of biotech shutdowns that simply did not progress far enough to attract capital. These seed-stage failures can arise for several reasons: inexperienced management (repeat entrepreneurs have consistently been found to be more successful the second or third time around), an inability to secure funding for R&D costs, and intense crowd competition. Many founders face their greatest hurdle at the "Series A Cliff," the gap between seed-stage enthusiasm and the rigorous clinical, commercial, and operational milestones required to attract institutional capital.

Zafgen

In 2015, metabolic disorder biotech Zafgen was one to watch. That January, the company's lead drug, beloranib, a MetAP2 inhibitor, showed a positive hypothalamic injury-associated obesity (HIAO) Phase 2 signal, and in May, the company announced a similar positive Phase 2 for beloranib in Prader-Willi Syndrome. A 12-week, double‑blind study in 17 adults met its primary endpoint (p < 0.01), with weight loss of up to ~11 kg from baseline; the company had progressed smoothly through the critical Phase 2 mark. The drug was supposedly advancing smoothly in Phase 3 trials when, in early October of 2015, the company abruptly canceled its appearance at an investor meeting, and didn't hold analyst or investor calls for days. The stock plunged nearly 60%.

Only days later, Zafgen announced that there had been a patient death in the Phase III trial, but refused to disclose details around the tragic outcome publicly. Months later, Zafgen acknowledged that yet another patient died of the same cause: pulmonary embolism. Two others experienced non-fatal deep vein thrombosis.

That December, the FDA escalated from partial to full hold on beloranib, and the following summer, the company was forced to reduce its workforce by 34%. President Patrick Loustau and CCO Alicia Secor also left the company. In July 2016, the company refocused on yet another MetAP2 inhibitor (ZGN‑1061). Despite Zafgen's claims of a safer new formulation, the FDA halted development of the drug in November 2018 based on the cardiovascular safety concerns identified in its predecessor's outcomes. Although Zafgen reached a July 2019 agreement with the FDA on an in vivo animal study design and protocol to establish relevant safety margins for ZGN-1061, preliminary results did not raise confidence in the Zafgen team, and on December 17th, 2019, Zafgen merged with Chondrial Therapeutics, having ended the year in a deficit of $396.4 million and no approved products. Zafgen now operates as Larimar Therapeutics.

What went wrong?

Three fundamental missteps stand out: ignorance of a predictable safety signal, opacity that destroyed investor confidence, and target class tunnel vision even after two deaths and an FDA clinical hold. Anti-angiogenic agents like beloranib had long been linked to thrombotic events; after the first patient death, however, the Zafgen team noted that "at the time, it was unclear if the death should be attributed to beloranib treatment," and the thrombosis-free patients were free to continue taking the drug in an open-label extension. Only after the second patient death did dosing stop; the Zafgen team later conducted mechanistic research suggesting "beloranib slows endothelial cell proliferation, which influences pro- and anticoagulant factors on the cell surface… prolonged exposure (≥ 12 h) from the suspension formulation is hypothesized to contribute to the imbalance of thrombotic events."

The company's secrecy also did not help its case. Zafgen's decision to cancel the investor roadshow and maintain what Fierce Biotech called an "awkward, stony silence" as safety rumors swirled around the beloranib program created an information vacuum that was inevitably going to be filled by speculation. Investors learned of the first patient death only after the stock had begun to slide, which only compounded the trust deficit when a second death was later disclosed. And the company's platform tunnel vision in the years following did not help their cause; rather than diversify, management poured scarce capital into a backup MetAP2 inhibitor (ZGN-1061), which investors and regulators could not credibly separate from beloranib's clot-risk baggage.

"Without such basic disclosures from the company [such as drug metabolization, cellular uptake, and clearance data], and the preclinical work showing that ZGN-1061 may induce pro-clotting factors… we have viewed the aforementioned variables as significant risks," commented Leerink Partners analyst Joseph Schwartz.

A decade after Zafgen's fall, Sarepta Therapeutics followed an eerily similar path. Fast forward a few years: Elevidys, Sarepta's AAV-based Duchenne gene therapy, won accelerated approval in 2023 and a label expansion in 2024 despite lingering FDA and critics' doubts. After two liver-failure deaths linked to Elevidys's viral delivery method, the company rebuffed regulators' demands to stop delivering product, then issued a press release about layoffs that omitted news of a third fatality, prompting Wall Street outrage when the omission surfaced days later and caused the stock to plunge 36%. In both cases, the opacity spawned shareholder litigation. A securities-fraud class-action suit alleges Sarepta made "false and/or misleading statements," failing to disclose that Elevidys posed "significant safety risks," that trial protocols were unable to catch severe side effects, and that the undisclosed morbidity would trigger trial halts, regulatory scrutiny, and jeopardise expanded approvals. While Sarepta remains in business for the time being, the twin stories underscore the importance of conservative clinical risk-benefit analysis and close monitoring of safety signals, especially of troublesome outcomes grounded in mechanistic rationale. Platforms and assets can be re-engineered; credibility cannot. Once forfeited, future developments and data are discounted, and capital moves on to the next racehorse.

Goldfinch Bio

When Third Rock Ventures unveiled Goldfinch Bio, a kidney disease precision medicine company, the biotech was set to be the first of its kind in the world of kidney disease therapy. Goldfinch launched in 2016 with $55 million, money that seeded development of the Kidney Genome Atlas (KGA) and an ion channel program aimed at CKD. Its lead candidate, GFB-887, targeted the TRPC5-Rac1 pathway to protect podocytes, the filtration linings of the kidney. In May 2019, Goldfinch also entered into a multi-billion-dollar milestone collaboration with Gilead Sciences. Five months later, in October 2019, Goldfinch acquired its second asset (CB1 inverse agonist GFB‑024) from Takeda. In 2020, Goldfinch raised $100 million in Series B, bringing its total capital raised to over $200 million in its first four years.

The shutdown came just under a year after the company released data from a Phase 2 showing that GFB-887's ability to reduce proteinuria compared to placebo was significant in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a rare kidney disease marked by blood vessel scarring in the glomerulus; however, the drug showed no effect in the initial cohort of 44 diabetic nephropathy (DN) patients.

Ultimately, DN was a disease that affected up to 40% of diabetics, and FSGS was an orphan indication (<40,000 U.S. patients) unlikely to justify a multibillion-dollar valuation on its own. The study was terminated in November 2022 due to "business reasons." At the same time, the company was already reducing its staff. The company released positive Phase 1 data on GFB-024 in late 2022, but the preliminary success was ultimately not enough to reassure investors after the lead candidate produced lukewarm results. Operations dwindled, and by January 27th, Goldfinch had officially closed.

What went wrong?

According to The Wall Street Journal, Goldfinch was attempting to secure additional funding before closure, but the previous Phase 2 failure posed too great a risk to investors. "Unfortunately, we had funding challenges, just like I think the rest of the environment, particularly private companies, in the current macro environment,” said CEO Tony Johnson. This explanation certainly played a part in the failure; the economic shutdown caused by COVID-19 heavily affected the biotech industry, and in a downturn, investors would move reasonably toward assets with quick de‑risking milestones; kidney precision medicine had neither in 2022.

However, another lesson is that indication selection matters as much as the mechanism. While the drug was safe and efficacious in both indications, FSGS, given its name, is a disease of the glomerular system; DN is a kidney-wide disorder affecting both glomeruli and tubules. Goldfinch Bio started out as a precision medicine company aimed at genetically defined, rare podocytopathies; pivoting to diabetic nephropathy, a highly prevalent, genetically heterogeneous disorder that would demand large, costly outcome trials, pulled the company far outside its original niche.

For $15 million upfront, and up to $520 million in milestones, Goldfinch was able to appease creditors somewhat by selling its TRPC4/5 channel candidates to Karuna Therapeutics, a biotech aimed at curing mood disorders. Ironically, however, Goldfinch collapsed just as the renal medicine market began heating up. Novartis alone has poured more than $5 billion into the space—in June 2023, the pharma bought out Chinook for $3.2 billion in IgA-nephropathy assets, followed by a $1.7B acquisition of Regulus Therapeutics two years later. AbbVie and Vertex Pharmaceuticals are both advancing frontier clinical-stage assets for ADPKD, and venture money has kept pace: early-stage renal biotechs like Renasant and Judo Bio are entering the arena with tens of millions in seed funding.

SQZ Biotechnologies

Armon Sharei was still an MIT graduate student when he discovered the technology behind SQZ. By pushing—or rather, "squeezing" cells (hence the name "SQZ") through microcapillary chips, a cell membrane could temporarily open enough such that proteins and reagents could enter without viral vectors or electroporation. Sharei spun out the company in 2013, branding the platform Cell Squeeze™, and was lucky enough to strike an early success most founders could only dream of. In December 2015, Roche offered SQZ a $1 billion option‑and‑license partnership deal. With Roche's stamp of approval, SQZ was able to raise substantial venture funding, culminating in a 2020 $65 million Series D and an October IPO via SPAC that same year.

At the time of the transaction, SQZ fielded three distinct therapies: APCs, AACs, and TACs, targeting infectious disease, cancer, and autoimmunity. The company acknowledged in IPO filings that Roche's milestone payouts were heavily dependent on the success of its first two clinical programs, SQZ-PBMC-HPV (Phase 1) and SQZ-AAC-HPV (preclinical), both aimed at HPV-positive tumors. Yet the company continued to stretch its platform further, announcing plans to expand into celiac and Parkinson's disease in the near future. Public updates stayed upbeat, but the company struggled behind the scenes as clinical progress faltered. By the end of 2022, the company finally announced a "strategic reprioritization" to focus solely on its lead HPV-targeting candidates and pause all other projects. Sharei and his CFO had left the company, the workforce was cut by 60%, and SQZ reported an 80% loss for the year. But the company suffered its biggest blow in 2023, when Roche declined to exercise its option on SQZ's HPV‑positive solid‑tumor program, and overnight, the billion‑dollar milestone stream that investors were waiting on disappeared.

The board was forced to gut 80% of the remaining workforce, leaving barely a dozen employees to keep trials alive. According to FierceBiotech, SQZ reportedly spent the remainder of 2023 searching for an alternative partner, but none came forward despite positive clinical results: eight of the twenty patients in SQZ's APC platform trial reported cancer stabilization. Bankers contacted 52 potential buyers; five signed NDAs, and three offered term sheets. Ultimately, Stemcell Technologies bought SQZ's IP on December 19th, 2023, for $11.8 million, and in March 2024, shareholders voted to liquidate. Undeterred, Sharei quickly regrouped, launching a new cell-engineering technology venture called Portal Biotechnologies in late 2023, which has thus far raised over $22 million in funding.

What went wrong?

As much as SQZ touted the $1 billion number from Roche, only $94 million of Roche's money had been received up to mid-2020; the vast majority of capital was contingent on long-term success (clinical, regulatory, sales milestones). And like many biotech startups at IPO, SQZ's prospectus admitted "we have incurred significant losses since inception and expect to incur significant additional losses for the foreseeable future, and we have no products that have generated any commercial revenue and we may never achieve or maintain profitability." This isn't unusual language for a pre-commercial biotech—SQZ was entirely reliant on investor funding and partnership payments to continue operating. However, SQZ's broad pipeline suggested dangerous dilution for a pre-revenue company, spreading limited resources across too many projects. An IPO framed around one or two assets would have set more modest expectations for investors. And amid the IPO frenzy, SQZ had still not settled on a defined company vision: platform or therapeutic.

Even in the best-case scenario (Roche staying on), the "alternate licensing" partnership structure meant SQZ would share rights and revenues for any success. Roche and SQZ would split commercial rights on alternating programs in oncology, and Roche held options on additional antigen targets. As SQZ's prospectus stated, success under the Roche collaboration "may be obtained at the expense of or to the detriment of our other wholly owned product candidates." While the Roche deal was an incredible early opportunity, it also implicitly capped SQZ's future profitability. Moreover, since that 2015 deal, Roche remained SQZ's lifeline. After noting the IPO cash would last only to 2022, the prospectus document states, "other than potential payments, if any, from our collaboration agreement with Roche for SQZ-PBMC-HPV, we do not yet have any committed source of funding for the completion of clinical development or commercialization of these product candidates."

Ultimately, the SQZ story demonstrates three critical lessons: contingent deals aren't cash equivalents, lead asset strength will always dominate preclinical pipeline breadth, and single-partner dependency can become an existential liability if diversification and fallback capital aren't in place.

Walking Fish Therapeutics

According to CEO Rusty Williams, M.D., Ph.D., Walking Fish Therapeutics, a B-cell therapy company with a three-asset portfolio, was two months away from requesting FDA approval to enter the clinic when an unnamed top investor pulled out at the last minute. The investor cited concerns over a long-term manufacturing lease; Walking Fish evidently lacked runway. The company had already begun plans to shutter when yet another insider followed the first investor out. Thirty-five employees were laid off, and Williams quite promptly moved on to his next venture at Ten30 Bio.

The May 2024 shutdown came as a public surprise. Walking Fish had closed a whopping $50M Series A (later increased to $73M) in early 2022, and had secured two ARPA-H grants just months before the shutdown. Walking Fish's lead candidate, WFX-001, aimed to cure Fabry Disease, a rare lysosomal storage condition. The company had plans to expand into other indications, envisioning a fully-fledged platform for B-cell-based therapies to restore malfunctioning protein and enzymatic activity, as well as reconstitute an innate antibody response in cancer therapy.

What went wrong?

While Williams did not disclose the funding split of the many investors in his Series B, the immediate collapse of the funding round after a single late‑stage lead investor withdrew suggests that Walking Fish had undertaken significant fixed costs, such as R&D and manufacturing expenses, based on anticipated, rather than secured, capital. This lack of adequate contingency financing meant they lacked the time to secure an alternative investor before running out of cash. As Williams admitted, "the cost of cell therapy manufacturing and associated clinical trial costs were difficult to overcome." "I think that B-cell therapy is likely to have its day; I think that what we were doing would have worked," said Williams in an interview with Fierce Biotech. "But it was just too expensive to get the phase 1 done in that financing environment."

Allakos

Founded in 2012, Allakos's lead candidate was AK002 (Lirentelimab), a monoclonal antibody targeting Siglec-8 (a receptor found on eosinophils and mast cells) to treat severe food allergies and inflammatory GI diseases. Altogether, Allakos's strategy was simple: to advance its lead antibody through clinical trials in multiple indications, demonstrate efficacy, and go public to fund Phase 3. The biological rationale was clear, as elevated eosinophils are known to play a role in disorders like eosinophilic esophagitis and gastritis. Novo Ventures led the company's December 2012 $32 million Series A investing with Roche and others. Follow-on early rounds added another ~$32 million, and a large $100 million Series B in early 2017 marked the last chunk of funding. By mid-2018, Allakos's lead program was progressing through a Phase 2 trial, and the company raised a $128 million IPO that summer, with the plan to put aside $94 million to advance AK002.

In mid-2019, the company announced positive Phase 2 results in patients with eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis, sending Allakos stock soaring. By late 2020 into 2021, Allakos's market cap swelled to the multi-billion-dollar range in anticipation of Phase 3 results. The trouble came in the fall of 2021, when two pivotal studies (Phase 3 ENIGMA-2 for eosinophilic gastritis or duodenitis, and Phase 2/3 KRYPTOS in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis alone) missed their co-primary endpoints despite successfully lowering eosinophil counts. That December, Allakos shares fell nearly 90%, wiping out approximately $3.5 billion in market value, and the company never recovered.

What went wrong?

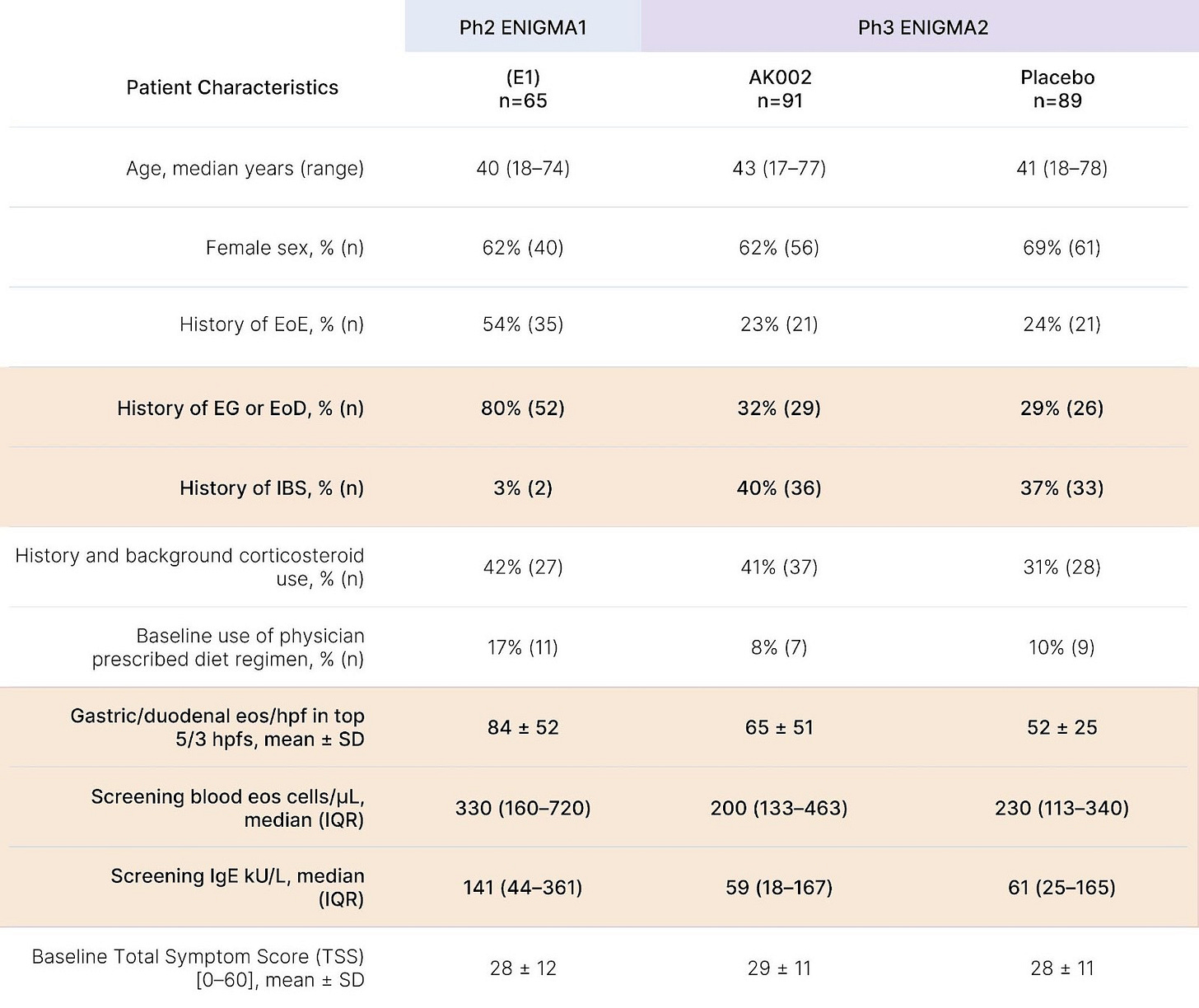

While eosinophil depletion offered an intuitively appealing biomarker, ENIGMA-1's Phase 2 reported only modest symptom improvements insufficiently robust to justify a Phase 3 investment. In Phase 2, treatment cut mean total symptom score (TSS) by a relative change of -48% vs -22% on placebo, yet when ENIGMA-2 used a more rigorous absolute change endpoint and a 6-item TSS (dropping two low-severity items from the 8-item diary), no clinically meaningful benefit emerged. Post-hoc analysis also suggests Phase 3 enrolled a broader, lower-severity population than the 17 legacy ENIGMA-1 sites, greatly increasing heterogeneity. Even ENIGMA-1's headline 63% "treatment response" rate (vs. 5% for placebo) was inflated by design, requiring both a >30% TSS reduction and a >75% histologic eosinophil reduction, anchoring the outcome to the very biomarker under evaluation.

Lastly, while a -22% symptom score reduction in ENIGMA-1's placebo arm might seem notable, such a drop was actually uncharacteristically low for this indication, where mean placebo improvement often approaches ~40%, a number not far off from lirentelimab's -48% figure. In ENIGMA-2, where histology and symptoms were treated as separate co-primary endpoints, placebo improved symptoms by ~45-50% (consistent with other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease trials), while Lirentelimab again failed to produce significant symptom benefit despite achieving an 80-90% eosinophil reduction versus placebo.

Only in 2023 did Kliewer et al. find that eosinophilic oesophagitis pathology is largely independent of excessive eosinophil production, which should have suggested to Allakos that this would be true for other indications. However, management pivoted to AK006 (an anti‑Siglec‑6 that would inhibit mast cell activity to reduce eosinophils indirectly) and continued developing Lirentelimab in atopic dermatitis (ATLAS) and chronic spontaneous urticaria (MAVERICK). Both failed in early 2024:

ATLAS: 23% of Lirentelimab vs. 18% of placebo patients achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index.

MAVERICK: Urticaria Activity Score dropped 27% in treated patients vs. 26% in placebo.

Allakos's downfall stemmed from a failure to interrogate core mechanistic assumptions, adapt clinical endpoints and trial design to prioritize patient-relevant outcomes, and recalibrate its strategy as the biological picture evolved, recognizing that while its products excelled at reducing eosinophils, functional outcomes faltered. Even after new evidence emerged, the company continued to hinge its pipeline on Siglec‑targeted antibodies aimed at modulating these cells indirectly.

Clinical trial misalignment was only exacerbated by operational excesses. Allakos aggressively scaled operations, incurring net losses of $246.1 million in the first half of 2022 alone, nearly double those of the previous year. By mid-2022, the deficit stood at $859 million. Allakos was forced into a rapid restructuring that February (termed the "Reorganization Plan"), terminating its substantial manufacturing commitments with Lonza AG and cutting ~35% of its workforce. While these actions slightly extended runway, they came too late to alter the company's trajectory. When alternative asset AK006 (a Siglec-6 activator) failed this January 2025 in a chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) trial, Allakos shrank to 15 employees and merged with Concentra Biosciences in April.

Sirtris Pharmaceuticals

In April 2008, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) agreed to acquire David Sinclair's spinout, Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, for ~$720M cash to access the company's lead sirtuin asset (SRT501) for metabolic and degenerative diseases. Notably, GSK paid this price at an 84% premium—that is, at a price 84% greater than the company's pre-acquisition valuation. Critics commented that the GSK acquisition was naïve, as the company had only a single compound in trials (SRT2104 in Phase 1b for ulcerative colitis), and there was insufficient evidence for human efficacy.

The mechanistic premise became even more controversial after Pfizer and other groups (Amgen, University of Washington) increasingly failed to replicate Sincair's data. In May 2010, GSK suspended a Phase 2a trial of high-dose micronised SRT501 in advanced multiple myeloma after several patients developed nephropathies; as GSK told FierceBiotech, the compound "may only offer minimal efficacy while having a potential to indirectly exacerbate a renal complication common in this patient population." Finally, in late November 2010, GSK ceased all programs related to SRT501, but stated that they remained interested in developing SRT2104 and SRT2379, biosimilars to SRT501 with "more favorable properties." By 2013, GSK shut down Sirtris's Cambridge lab, and the company was effectively dissolved into GSK's R&D.

Unfortunately, a 2014 trial found that a 28 day course of SRT2104 had no protective effect in type II diabetes patients, nor ulcerative colitis in a 2016 trial, and SRT2379 was unable to modulate the inflammatory response of healthy male subjects after exposure to lipopolysaccharide (however, SRT2104 did prove successful in stimulating anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant responses in a later trial). In any case, no Sirtris compounds advanced quickly enough within GSK, and the pharma company seemingly let go of the sirtuin platform after 2015. While many other groups in the years following have continued exploring new indications for compounds in the SIRT-1 activator class, a sirtuin activator has yet to be approved and deployed into the market more than 25 years after Sincair's initial yeast aging discovery.

What went wrong?

The Sirtis story represents both a lesson to founders and investors. Paying an 84% premium for a platform with unvalidated data put GSK in a problematic position when third‑party labs contradicted Sirtris's SIRT1 activation data; ultimately, GSK should have reproduced the company's data independently before writing a nine‑figure check. On the other hand, Sirtris should have controlled for assay artifacts. Pfizer's study found that Sinclair's activator compounds bound to the SIRT1-fluorescent peptide complex, but when they removed the fluorogenic group, calorimetry confirmed that the compound only bound to the artificial peptide-enzyme complex and not SIRT1. GSK may have been able to get ahead of the criticism by imposing a more stringent post‑merger governance model; however, the pharma seemingly granted Sirtris full autonomy in Cambridge.

Athersys

Athersys spent more than two decades betting on MultiStem, which the company described as an "off-the-shelf" stem cell therapy designed to promote tissue repair and healing. Since 2011, the company had financed its moonshot through funding from Aspire Capital. In May 2022, Aspire agreed to buy up to $100 million of shares in the company over 24 months. Only a few weeks later, however, the company faced an overseas disappointment: a critical Phase 2/3 ischemic stroke trial sponsored by Healios, Athersys' Japanese partner, failed to meet its primary endpoint. The finding triggered a 60% share price collapse, prompting leadership to undertake a massive 70% reduction in staff mid-2022, gutting the company's R&D team with the intention of regaining investor trust by cutting costs. However, Aspire Capital Fund had only purchased shares with a caveat that it could cut and run under a range of circumstances, including the departure of any Athersys executives for any reason. Athersys's $100 million committed equity financing line was cut that July.

Hoping to salvage the program, the company persuaded the FDA in early 2023 to tweak its MASTERS‑2 design, shifting the primary outcome from a 90‑day functional score to a 365‑day measure, aiming to replicate encouraging long‑term trends seen in prior Japan stroke trials. However, after gaining FDA permission, Athersys reported in October 2023 that the results of an interim analysis proved the trial was still underpowered; 300 patients weren't enough to show efficacy, and Athersys could not afford to expand. At this point, Athersys's stock was a penny stock (quite literally trading at ~$0.14).

"Since announcing the results of the blinded interim analysis of MASTERS-2… we've been actively engaged in exploring strategic options with interested parties to determine the best path forward for MultiStem and Athersys," said Daniel Camardo, CEO. But options were slim. No partner stepped forward, and on January 5th, 2024, the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, selling its remaining assets to Healios.

What went wrong?

Athersys had been an established company for fifteen years, with over $500 million invested, and zero backup pipeline. MultiStem was Athersys's bread and butter, and their therapy of choice for every indication they pursued (stroke, trauma, ARDS). The company either misjudged Aspire Capital's commitment or overlooked crucial deal clauses, as layoffs executed without regard for financing extinguished $100 million in funding. And lastly, launching a pivotal trial in the same indication where a previous attempt had failed, based solely on aggressive statistical assumptions, boxed the company into a precarious corner.

Argos Therapeutics

Argos Therapeutics was a Durham-based biotech that spent over two decades developing Arcelis, an immunotherapy platform that aimed to leverage a patient's own dendritic cells and tumor RNA to create a metastatic kidney cancer (mRCC) vaccine (named rocapuldencel-T, formerly AGS-003). After success in Phases 1 and 2, Argos moved the therapy into a pivotal 2012 Phase 3 (ADAPT), combining rocapuldencel-T with the standard-of-care drug sunitinib in 462 patients. The study finalized enrollment in July 2015 and commenced treatment. However, in February 2017, an independent data monitoring committee (IDMC) analyzed interim results and recommended the trial be stopped for futility, as the vaccine was "unlikely to demonstrate a significant improvement in overall survival."

Nonetheless, Argos persisted. But 2018 data remained negative (in fact, the data were somewhat disappointing—median overall survival was slightly longer in the sunitinib arm than in the combination arm (28.2 months vs. 31.2 months). Finally, the company shut down ADAPT. NASDAQ delisted the stock in spring 2018 after trading below the minimum threshold, and Argos was forced to lay off another 20 people that year. In November 2018, Argos filed for bankruptcy. Argos had been simultaneously running HIV trials with AGS-004, but a Phase II study in acutely treated HIV patients saw no evidence that the vaccine enabled stopping ART, and a UNC/Argos pilot trial combining AGS‑004 with vorinostat also failed to induce greater HIV-specific immune responses. In a 2019 court-supervised asset auction, Argos's remaining technology was sold to a consortium of two Korean biotechs that included its former partner Genexine.

What went wrong?

Instead of heeding third-party evaluations, Argos sought to buy time, proposing a protocol amendment to the FDA to continue the study with some changes, and in April 2017, the FDA acquiesced. Instead of taking the failure in stride, Argos's decision to move regulatory goalposts instead of rethinking its pipeline locked stakeholders into a dead program and consumed capital that could have funded a more promising candidate or pipeline-rescuing acquisition.

Takeaways

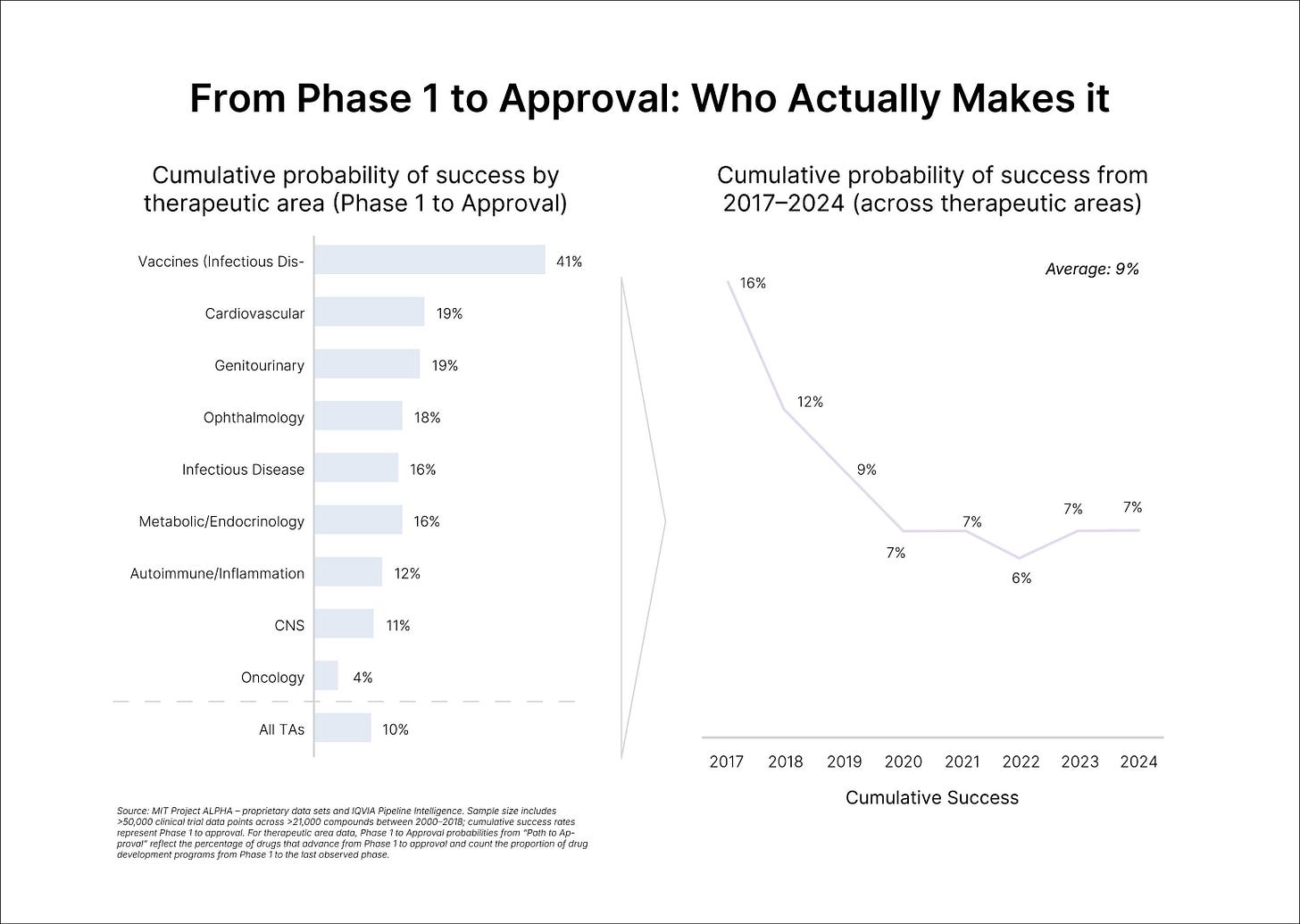

The grim baseline is well known. Only one in every 5,000 compounds (0.02%) discovered and tested preclinically get approved; of the drugs started in clinical trials in human participants, only 10% would secure FDA approval. In a later analysis of the period between 2014 and 2023, Citeline estimated the average likelihood of approval (LOA) for a new Phase I drug to be 6.7%, an all-time low. According to Citeline, the leading cause of failure remains the "Phase II hurdle," with a 28% completion rate compared to Phase I (47%) and Phase III (55%).

Yet molecules are only half the story; many companies fail for reasons that have little to do with science. For some fledgling companies, lack of access to supply chains, industrial-scale CMC expertise, and regulatory teams sink the startup rather than drug efficacy; it is mainly for this reason that securing a corporate partner can be the decisive bridge to carry a program through trials. In a study in Nature Biotechnology, analysts from two Dutch venture firms mined GlobalData's Pharma database for every large‑pharma/biotech startup deal made between 2004 and 2019. They then asked whether prior pharma ties predicted startup "success," defined as going public, being acquired, or securing at least one drug approval during that window. Startups with a large‑pharma investor to guide operations nearly doubled their median odds of success (37% vs 18%) and achieved bigger outcomes—market cap rose from $138M to $332M, and median acquisition value from $136M to $377M.

According to Fierce Biotech, venture failures peaked in 2023 with 27 closures, which dropped to 22 in 2024; sources have yet to compile data on how well biotechs fared in 2025, although age1's analysis tallied 15 as of August 14th. However, the same reasons for failure arise year after year. In 2022, BioSpace interviewed several CEOs and VCs on this topic: many mentioned overlapping themes: poor capital management, inadequate flexibility, and miscommunication across hiring, development, management, and more. It's worth stating clearly that most biotechs do not fail because their founders are inept or their science is faulty. In fact, the opposite is true—the companies profiled in this piece were founded by credible, well-intentioned teams and built around plausible mechanisms. Still, building in biotech, for the reasons outlined above and more, is brutally hard. More specifically, failure is far and beyond the statistical default. Some of these companies did not fail from one single decision, but a series of missed pivots, unhedged assumptions, and cracks that gradually widened over time, whose consequences were only visible in hindsight.

Ultimately, our analysis of biotech failures reveals that clinical readouts are rarely the only cause of shutdown. While disappointing clinical trial outcomes are the most ubiquitous catalysts for a biotech's downfall, what separates those who can bounce back from those who can't is behind-the-scenes operations. Importantly, operational robustness can sometimes overcome scientific setbacks (e.g. Exelixis's strategic reprioritization post-COMET-1 trial failure). Conversely, operational blunders can sink even scientifically promising ventures (e.g. Dendreon's miscalculation of demand, COGS, and CMC for prostate cancer treatment, Provenge).

One factor that separates survivors from casualties is whether management aligns trial endpoints with true patient benefit. Allakos drove eosinophil counts down, yet ignored tepid symptom data; its pivotal ENIGMA‑2 study missed both co‑primary clinical endpoints and imploded a multi‑billion‑dollar valuation. While biomarker wins are necessary, they are never sufficient. Clinical rigidity (likely a byproduct of belief in the sunk-cost fallacy) also remains a major driver of biotech failures: Argos pressed on with their renal‑cell vaccine after a data‑monitoring committee declared futility. An extra year of spending only confirmed the verdict and left little capital for a pivot. Those with a long-term vision, including plans for expanding into new indications or developing additional assets beyond their lead candidate, will consistently outperform startups focused solely on short-term goals.

Balance sheet architecture is another tripwire. Walking Fish relied on a single late‑stage investor and spent against money that was not yet in its pockets; when that backer walked, the Fish couldn't: fixed costs outpaced runway, and the company closed despite a recent $73 million raise. Athersys, by contrast, conducted a mass layoff to cut costs after a stroke trial failed, breaching the fine print on a $100 million equity financial agreement. Contingency capital is an inevitable and essential source of funds, but can never be relied upon to the extent that a loss of such funds would bring down the company.

Overdependence on single partnerships also remains a source of caution. While SQZ publicized a "$1 billion" Roche alliance, only $94 million was ever wired. When Roche declined its option, it led to liquidation. Investor trust is equally essential. Zafgen's decision to withdraw from an investor conference after a trial death and stay silent for days was significantly damaging; the stock had already lost half its value by the time management confirmed the fatal thrombotic events. Even if transparency can't revive bad data, opacity compounds the damage.

Another recurring error is letting valuation outpace validation. GSK paid an 84% premium to acquire Sirtris on the strength of unreplicated assays; subsequent independent work showed the lead compound bound to an artificial fluorescent substrate, not to SIRT1 itself. By the time Sinclair could publish a rebuttal, it was too late—the program was abandoned within five years. Ultimately, a late‑stage independent diligence repeat can turn out to be cheaper than a nine‑figure investment.

Across these cases emerge consistent patterns: financial mismanagement, communication failure, over-reliance on single partners, clinical rigidity, and more. While addressing these factors can't guarantee success, they do significantly influence whether a missed primary endpoint becomes a temporary setback or an obituary. Stay tuned for Part II: next week, age1 will publish a systematic review of 64 publicly disclosed biotech shutdowns (2023–2025), organized into six root-cause clusters, alongside an operator checklist we believe every founder should use as they build.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Alex Colville for providing guidance wherever necessary, and thank you to Lily Clayton for thoughtful graphic design! Lastly, thank you Bruce Booth at Atlas Ventures for inspiring this piece, and to Michael Reisman for his work designing and generating the data for Figure 2 (“From Phase 1 to Approval: Who Actually Makes It”).