Hunting Targets in Their Native Environment

Betting on Biology III: A strategic framework for context-preserving target discovery

In January 2026, Gordian Biotechnology and Pfizer announced a research collaboration to apply in vivo mosaic screening directly within visceral adipose tissue for obesity target discovery. The platform enables pooled genetic perturbation screens in epididymal and retroperitoneal white adipose depots: fat tissues that orchestrate systemic metabolic signaling through hormone secretion (leptin, adiponectin), lipid trafficking (free fatty acids), and immune cell recruitment (tissue-resident macrophages). According to Gordian CEO Francisco LePort, the company had no obesity program a year prior; after initiating work in early 2025, they successfully translated the platform, completed initial screens, and began identifying novel targets within four months.

This speed matters commercially, but not because obesity represents a “post-GLP-1 market” as GLP-1 receptor agonists currently dominate obesity pharmacotherapy. Rather, the market now demands targets that address three specific unmet needs GLP-1s cannot solve: (1) the 9-27% non-responder rate, (2) the 25-40% lean mass loss that accompanies fat reduction that is particularly problematic in older adults where sarcopenia compounds frailty risk, and (3) the 37-81% one-year discontinuation rate driven by cost, insurance type, comorbidities, and absence of type 2 diabetes etc. These gaps create commercial space for mechanistically distinct targets, particularly those addressing adipocyte biology, metabolic memory, or muscle-sparing pathways.

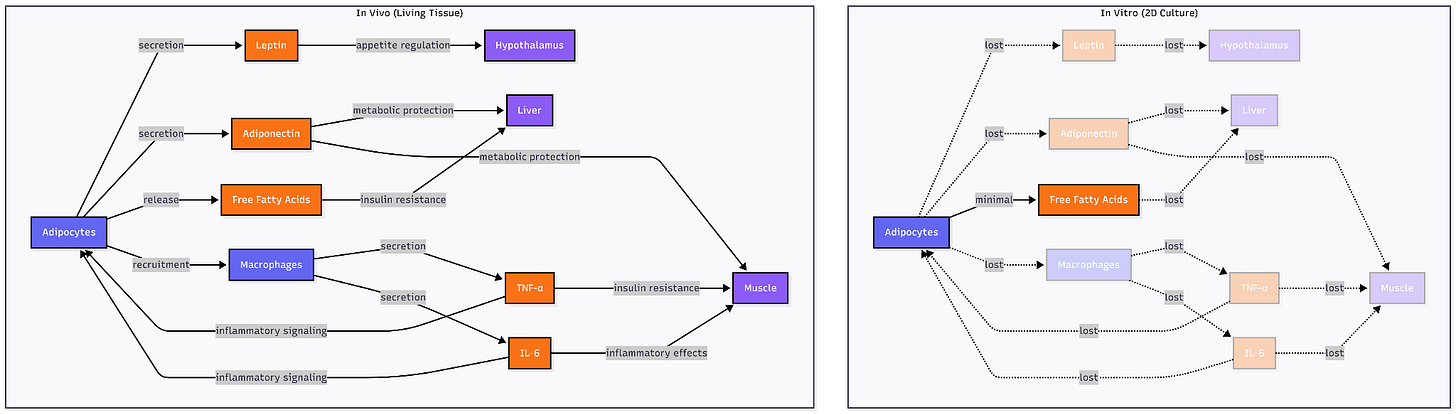

The platform choice reveals a testable hypothesis about chronic, age-related disease target identification: that physiological context is a NEED. Traditional 2D adipocyte cultures fail to recapitulate the insulin resistance phenotype central to metabolic disease; co-culture with macrophages in 3D systems is required to observe reduced glucose uptake and impaired GLUT4 translocation characteristic of inflamed adipose tissue. More fundamentally, in vitro systems, even sophisticated vascularized 3D adipose tissue models cannot fully replicate the in vivo environment as the constitutive elements (hormones, cytokines) exist at fixed concentrations rather than the dynamic, responsive levels found in living tissue.

We need to think about whether this gap between simplified systems and living biology actually matters for target identification. For some diseases, it often does not. Cancer cell survival screens, ion channel pharmacology, and receptor-ligand binding assays work in isolated systems because the relevant biology operates at the molecular level. The target either blocks a specific enzymatic reaction or it does not, the complex tissue environment in these circumstances adds noise instead of signal.

Age-related metabolic diseases may occupy a different territory. Visceral adipose tissue secretes leptin that regulates hypothalamic appetite circuits, releases free fatty acids that drive hepatic insulin resistance, recruits macrophages that sustain inflammatory signaling through TNF-α and IL-6, and responds to sympathetic innervation controlling lipolysis. An adipocyte on plastic loses mechanical tension from extracellular matrix, paracrine signals from neighboring pre-adipocytes and immune cells, endocrine inputs from distant organs, and vascular perfusion delivering nutrients and immune factors. Whether these features are signal (revealing therapeutic targets invisible in reductionist systems) or noise (obscuring molecular mechanisms) determines which experimental platform can distinguish causal drivers from the vastly larger set of genes that correlate with disease readouts in simplified models but prove irrelevant in human pathophysiology.

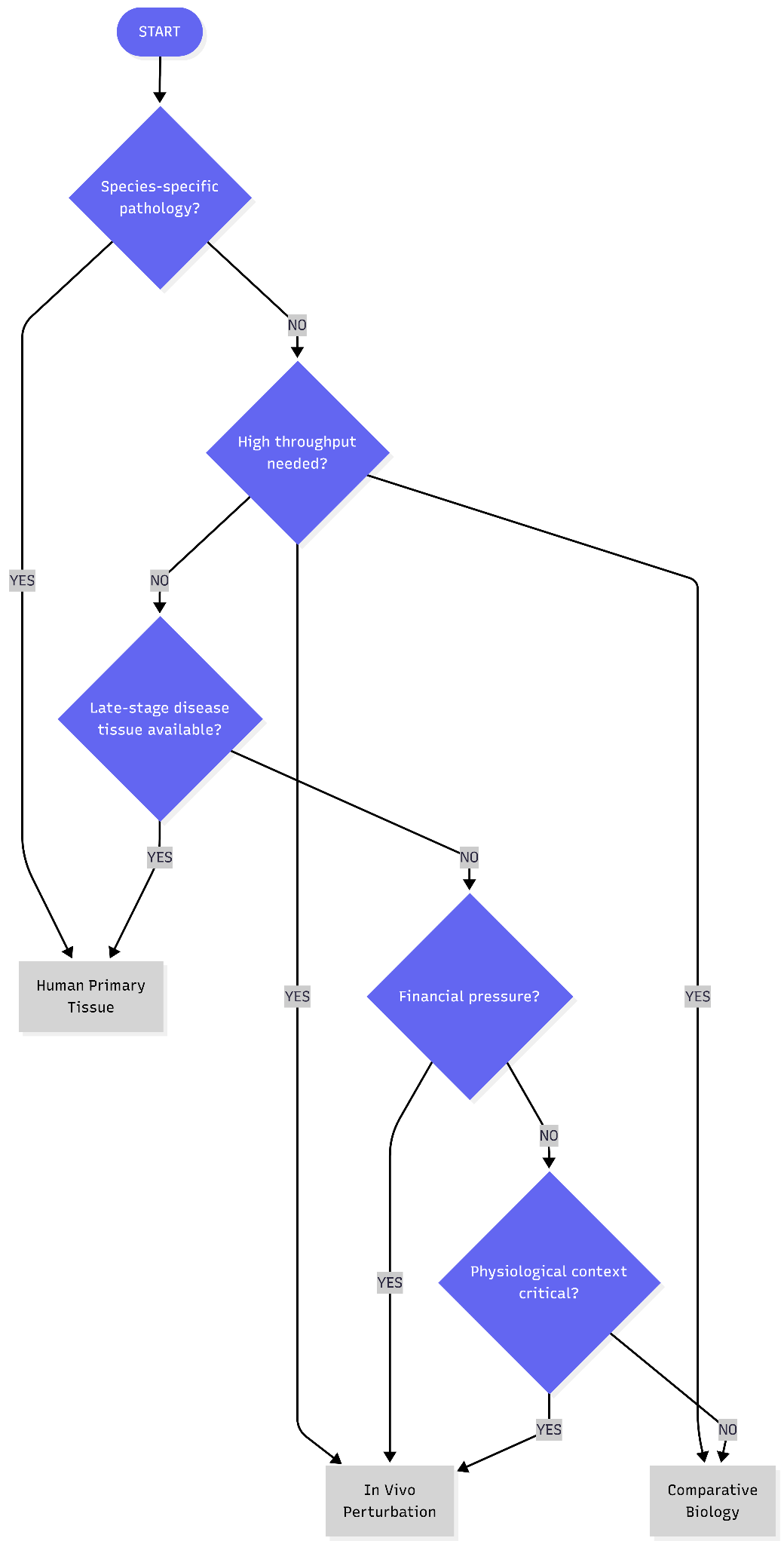

Three strategies have emerged attempting to preserve physiological context:

In vivo perturbation at scale

Human primary tissue perturbation platforms

Comparative and evolutionary biology

What follows is a systematic analysis of these three approaches: the evidence supporting each, the failure modes that undermine them, and the criteria for determining when physiological context genuinely improves target identification versus when it adds cost and complexity without increasing the probability of finding causal drivers.

In Vivo Perturbation at Scale

As we defined perturbation at scale in our last piece, this method highlights the in vivo element. In practice, this means delivering a library of perturbations (e.g. CRISPR guides, shRNAs or cDNAs) into a disease-relevant model, then measuring each cell’s “barcode” and phenotype (often by single-cell RNA sequencing) to link interventions to outcomes.

Gordian Biotechnology has pioneered this “mosaic” tissue approach to test hundreds of gene therapies simultaneously within a single animal. The platform’s success really comes down to three things:

Pool delivery: Gordian injects hundreds of AAV vectors (each targeting a specific gene) at low dose into the tissue of an aged or diseased animal. The low multiplicity of infection ensures that most cells pick up only one perturbation, creating a true mosaic of treated and untreated cells.

Tissue specificity: Each viral construct uses cell-type-specific promoters or serotypes so that only the desired cells are edited.

Barcode tracking: Each vector carries a DNA or RNA barcode unique to its perturbation. After treatment, the tissue is dissociated and subjected to single-cell (or single-nucleus) RNA sequencing. In the sequencing data, the barcode reveals which perturbation each cell received, while the transcriptome reports that cell’s response.

This high-resolution readout offers two distinct benefits:

Cellular resolution: It distinguishes effects across subpopulations (e.g., separating mature adipocytes from stem cells or infiltrating macrophages) within the same tissue.

Rich phenotypic mapping: scRNA-seq captures shifts in thousands of genes instead of simple survival. This allows for deep analysis of pathway-level readouts, such as inflammation, insulin signaling, and fibrotic remodeling.

Gordian applied this platform to identify targets in obese, aged mice on a long-term high-fat (”GAN”) diet. By targeting hundreds of genes in visceral fat, they identified interventions that shifted the aged transcriptome toward a “rejuvenated” state. Knocking down certain genes induced a ‘beiging’ of fat cells and improved insulin signaling, and other targets reduced lipid synthesis or inflammation in the tissue.

Limitations of the approach:

Interpreting “rejuvenation”

As delineated in Part II of the series, signatures of rejuvenation need to be analysed more critically. A “more youthful” transcriptome might be defined by comparison to young healthy tissue (lower levels of inflammatory and senescence genes, etc.). However, the signatures risk failing to improve organismal health or lifespan when tested long-term. A perturbation might down-regulate certain age markers simply by activating stress responses or by causing cell turnover, without truly restoring function.

Delivery

In vivo screens rely on viral vectors or nanoparticles with limited tropism (e.g. poor blood-brain barrier crossing, liver accumulation, exclusion from large or fibrotic tissues), and far fewer cells can be transduced or recovered than in vitro, limiting library size and statistical power.

The host immune system can neutralize vectors or eliminate perturbed cells via pre-existing anti-AAV antibodies or immune responses to Cas9, reporters, or newly introduced proteins, causing loss of signal and unintended inflammation.

Cellular heterogeneity

Transduction is invariably uneven, some cell types or regions get many perturbations while others get none. After treatment, tissue dissociation and single-cell capture introduce bias: certain fragile or large cells (e.g. aged neurons, adipocytes) may die or fail to encapsulate, so the sequenced population is not a random sample of the in vivo pool.

Likewise, droplet-based scRNA-seq only captures a fraction of each cell’s mRNAs (including the perturbation barcode), so many perturbed cells may yield no readable guide sequence. Separately, even if a guide RNA is detected, the genome editing it induces may be incomplete: cells may have 0, 1 or 2 alleles cut, and there is no easy single-cell readout of editing efficiency.

Model-dependent limitations

Mice differ from humans in immunology, metabolism, gene lifespans, etc. In a notable example, all human myeloid leukemia-specific targets would be missed by mouse screens simply because the relevant gene is not expressed in mice (Consider: humanized systems?)

How to stress-test this approach?

Dose-responsiveness: A true causal target generally shows graded effects with perturbation strength (e.g. varying AAV dose or guide efficiency).

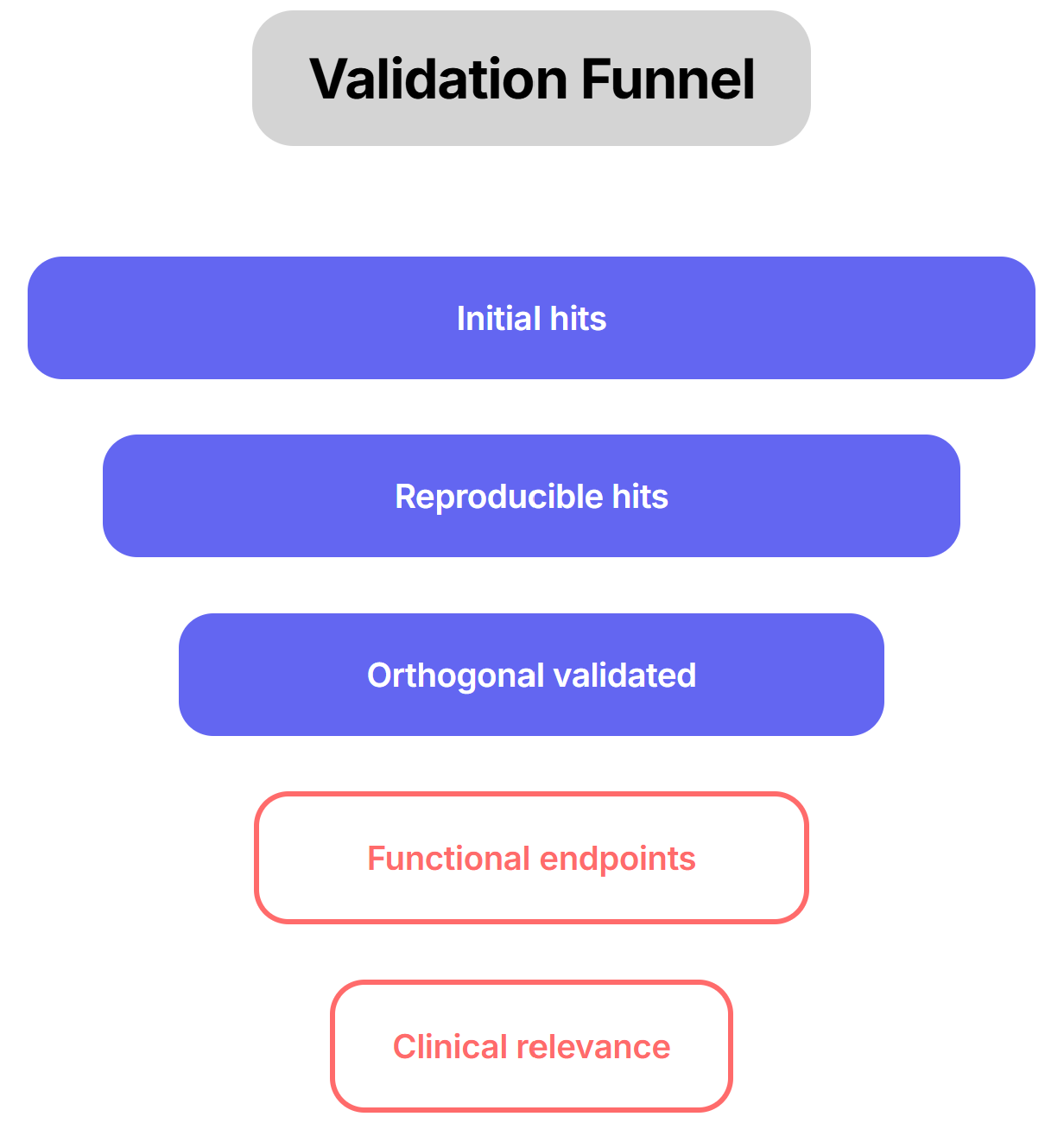

Orthogonal assays: Said it in other parts of the series, just can not emphasize enough. For example, if a CRISPR knockout yields a beneficial transcriptional shift, demonstrate that restoring the gene’s expression (genetic rescue) or using an independent modality (e.g. RNAi or a small-molecule ligand) produces the opposite effect. Such paired perturb-and-rescue helps confirm on-target action. To use the Gordian example, they followed up promising hits by administering them (as single-gene gene therapies) at full dose and looking for actual phenotypic improvements (e.g. better glucose tolerance, reduced fibrosis, improved heart function). Only if an intervention not only reprograms the gene expression profile and yields measurable functional gains can one be confident it represents a genuine rejuvenation. We need to emphasize functional endpoints.

Cross-validate in different models: Validating hits in human-derived organoids or primary tissues is particularly essential to confirm that the regulatory networks are evolutionarily conserved. Ultimately, triangulating results across diverse genetic backgrounds helps determine if a hit is a universal driver or merely dependent on a specific genetic modifier landscape, which is crucial for predicting success in a heterogeneous patient population.

Ex-vivo Human Primary Tissue Perturbation Platform

Human primary tissue perturbation platforms use real human tissues (e.g. donated organs, biopsies, or primary cell cultures) as the testing ground for potential treatments.

*Aim: Identify targets that have immediate human relevance

Fresh human tissue, often 100 to 500 µm thick, is cultured under oxygenated conditions to maintain its 3D structure, native extracellular matrix, and all the types of cells it contains. Ochre Bio, a startup focused on liver disease drug discovery, has created a platform based on this concept. It generates large-scale perturbation profiles in human livers and hepatocytes, including genome-wide gene knockdown in primary hepatocytes and single-cell profiling of perfused donor livers, to facilitate target discovery. These platforms fall between simple in vitro tests and animal studies. They maintain human-specific multicellular complexity while allowing for experimental control. Many liver and lung diseases are highly species-specific, so these models fill an important gap in perturbational biology by providing validation in a human context. This strategy already produced two rich datasets with GSK: one mapping gene knockdowns to expression changes in human hepatocytes, and another profiling the cell-type-specific gene expression of perfused diseased livers.

Limitations of the approach

Ethical and regulatory constraints (especially for solid organs)

Access to human organs is limited to surgical waste, transplant discards, or end-stage diseased tissue, because sampling healthy organs or performing repeated biopsies for research is ethically impermissible. Consequently, most platforms operate on late-stage, highly perturbed biology rather than early causal disease states, introducing systematic sampling bias.

Informed-consent, privacy, and biosafety regulations restrict permissible perturbations, longitudinal studies, and data sharing (e.g. limits on genome-wide editing, chronic culture, or clinical linkage). These constraints truncate experimental time horizons and narrow the searchable biological space independently of technical feasibility.

Limited viability and throughput

Slices typically remain viable for only a few days (often 2-5 days) before hypoxia and nutrient gradients degrade function. Longer assays are infeasible. This contrasts with permanent cell lines or organoids that can be passaged indefinitely. Likewise, because each experiment requires fresh human tissue, throughput is low: only tens of slices can be prepared per sample, and scaling to hundreds of perturbations is challenging.

Tissue access

Reliable access to fresh human tissue can be a bottleneck (need donor organ or surgical samples). Samples come from individual patients, so biological variability is high. Intrinsic heterogeneity (cell composition, fibrosis grade, tumor content) means inter-slice and inter-donor reproducibility is limited. For example, the same tumor sliced from different areas or donors can yield different responses, making trends harder to detect. This “real-world” variability must be controlled by using multiple donors and replicates.

Delivery constraints

Genetic perturbation in thick tissue is nontrivial. Transducing all cells with CRISPR or shRNA vectors may be inefficient or uneven, especially in the core of a slice. Similarly, large biologics or nanoparticles may penetrate poorly. Slice size (few hundred µm) is a tradeoff: thick enough to preserve cells, but thin enough for diffusion. In practice, diffusion limits mean that drug delivery and genetic editing efficacy can vary across the slice.

Experimental complexity

Because slices are complex, data analysis is more challenging. Background cell heterogeneity, matrix autofluorescence, and variable oxygenation all add noise. Multimodal assays (scRNA-seq, imaging, ELISA, etc.) must be carefully controlled. Moreover, standardization is difficult: there are few consensus protocols for slice culture and analysis, leading to batch-to-batch variability.

All these factors limit reproducibility compared to simpler systems.

How to stress-test this approach?

Benchmark against known human data: Wherever possible, compare slice responses to existing in vivo or clinical data. For example, test a perturbation with a known human outcome: if an antifibrotic drug ameliorates markers in slices similarly to patient or animal data, that builds confidence. In a liver PCLS study, the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib produced the same antifibrotic gene-expression changes in slices as observed in prior cirrhosis models. Likewise, demonstrating a slice’s sensitivity to a standard therapy (e.g. the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin reduced PDAC slice proliferation) shows the model can recapitulate expected drug effects.

Replicate across donors and timepoints: True effects should persist across tissue from multiple patients and across independent cultures. Time-course analysis helps ensure the effect is not a transient stress artifact. Lack of signal reproducibility is a red flag for a technical artifact.

Rescue assays: Whenever possible, perform complementary “rescue” experiments. For instance, if knocking out Gene X in slices induces pathology, reintroducing a wild-type copy or adding a pathway agonist should reverse the effect. Conversely, applying an independent perturbation (e.g. a small molecule versus genetic KO) targeting the same pathway provides convergence. Orthogonal readouts are also critical: verify gene expression changes with protein-level assays or histology. In practice, slice studies measure both molecular and functional endpoints. For example, drug-treated liver slices might show downregulation of proliferation genes by RNA-seq and decreased Ki67 staining by IHC, or altered metabolite levels by mass spectrometry. Such multi-layer validation (gene, protein, phenotype) guards against false positives.

Compare to clinical endpoints: When possible, link ex vivo findings to patient data. For example, if a slice perturbation upregulates a fibrosis gene signature, check if that signature predicts fibrosis severity in patient cohorts or is known from GWAS. Aligning slice biomarker changes with human pathology strengthens causal claims. This might involve correlating slice-derived profiles with public datasets or biobank samples.

Comparative/Evolutionary Biology

Comparative and evolutionary biology-driven discovery mines the traits of long-lived or disease-resistant species (and extraordinary humans) to find mechanisms that could be turned into therapies by examining comparative gene expression, regulatory regions, protein modifications, evolutionary conservation, stress-response pathways etc.

The premise is that nature has already solved many problems: some animals naturally don’t get diseases that afflict humans, or survive conditions (freezing, low oxygen, radiation) that would normally kill human cells. The underlying genes, proteins, or pathways responsible can be identified and then mimicked or activated in humans.

Cancer resistance: An elephant has roughly 100-fold more cells than a human and lives as long, yet its lifetime cancer mortality is only ~5% (versus up to ~20-25% in humans). The discrepancy is known as Peto’s paradox. A major reason appears to be an evolutionary expansion of the tumor-suppressor gene TP53. Whereas humans have a single TP53 gene, elephants carry at least 20 copies (including 19 retrotransposed duplicates) that are actually expressed. Extra TP53 means extra dosing of p53 protein guarding the cell and elephant cells undergo apoptosis in the face of DNA damage at roughly double the rate of human cells, before cancer develops. Now the translational step is to harness this mechanism for humans. Peel Therapeutics, for example, is developing therapies around elephant p53 (“EP53”) to recapitulate this hyper-apoptotic, cancer-suppressing phenotype in human tissues.

Stress tolerance: Cross-species genomics is yielding therapeutic insights as well. Fauna Bio, for example, studies hibernating mammals to find factors that could protect human organs from disease, and has established strategic collaboration with Eli Lilly for its platform. Hibernators like the 13-lined ground squirrel endure extreme metabolic suppression and even near-freezing body temperatures for long periods, entering states akin to severe ischemia, but their organs (heart, brain, kidneys) exit torpor undamaged once they rewarm. By comparing gene expression in such animals, Fauna’s team identified one gene, code-named Faun269g, that stood out as a driver of multi-organ stress tolerance. By studying how a hibernating species naturally avoids heart failure under harsh conditions, researchers uncovered a promising drug target (and a following lead compound) now moving through preclinical development.

Musculoskeletal health: Many adaptations identified through evolution already have built-in safety and efficacy. Hibernating grizzly bears provide a robust proof of concept for osteoporosis treatment by maintaining structural bone integrity through a biological mechanism that prevents the disuse-atrophy seen in other mammals. They bypass the “use it or lose it” paradigm by reducing cortical bone turnover activation frequency by 75% while maintaining a strict homeostatic balance between formation and resorption. This balanced turnover, likely mediated by PTH signaling that prevents osteocyte apoptosis and suppresses osteoclastogenesis, validated sclerostin as a high-confidence target for therapies like Romosozumab.

Comparative screens can also flag mechanisms that never vary in our species (e.g. an embryonically lethal tweak in humans). A comparative genomics analysis of 57 mammals, for instance, linked longevity to enhanced protein stability and demonstrated that such comparative hits reveal human lifespan biology. Additionally, if independent long-lived lineages share a genomic feature, it’s likely fundamental. For example, the insulin/IGF-1 pathway is repeatedly implicated in lifespan regulation from worms to whales.

Limitations of the approach

Phylogenetic gaps

Animals vary enormously in lifespan and life history. Comparing organisms whose lifespans differ by orders of magnitude (a 2-day mayfly versus a 200-year whale) adds statistical and conceptual complexity. It can be hard to align aging metrics or isolate the right comparisons, so findings may reflect confounders (body size, metabolic rate, etc.) rather than causal mechanisms.

Model tractability

Many species with exceptional biology are difficult to study. Large or long-lived animals (whales, elephants) pose obvious husbandry challenges, while even small exotic models (naked mole-rats, bats) have specialized needs. There is a difficulty in finding animal models that both emulate human aging processes and are practical for the lab. If a candidate adaptation can’t be experimentally tested (for example, because no lab animal shares it), its value remains speculative.

Translation gap

Not all evolutionary solutions map to humans. Many longevity-enhancing variants in other mammals have no human equivalent, or were fixed (and invisible) in our lineage. One comparative-genomics study found little overlap between genes identified in long-lived mammals and human GWAS signals for lifespan. In other words, a “hit” from an animal screen might not be druggable in people or might simply reflect evolutionary chance.

Context specificity

Adaptations often serve species-specific niches. For example, a gene that protects a burrowing rodent from low oxygen has no obvious parallel in human biology. Comparative hits must be evaluated in context: some mechanisms may be irrelevant outside the original evolutionary setting. In short, this approach works best when it focuses on broad, conserved processes (e.g. DNA repair, metabolism) and is less useful for pathologies rooted in uniquely human traits.

How to stress-test this approach?

Phylogenetic replication: Demand that a candidate emerges independently in multiple lineages. Rigorous screens can compare the top and bottom deciles of species by lifespan or stress-resistance, then require that each candidate feature is fixed in all “long-lived” groups and absent (or different) in “short-lived” ones. Permutation or phylogenetic ANOVA tests are then applied to confirm significance, ensuring the signal isn’t due to shared ancestry or chance.

Human-data alignment: Check whether the candidate gene or pathway shows any relation to human aging or disease. If possible, examine human genetic or clinical data: do variants in the target correlate with healthspan? Is the gene expressed or dysregulated in patient tissues? This cross-check guards against chasing species-specific quirks.

Functional validation: Test the target in relevant living models. For a gene identified in elephants or hibernators, one might use CRISPR or drugs in human cells or mice to mimic the predicted effect. For example, overexpress the long-lived species’ version of the gene (or knock down its human ortholog) and measure outcomes: cell stress resistance, metabolic function, or neuronal survival. Success in multiple assays increases confidence that the target truly drives the desired effect.

Diverse phenotypic assays: Use *orthogonal readouts. If a target is supposed to improve metabolism, verify effects on both molecular markers (insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial function) and organismal health (weight, endurance) in animals. For neurodegenerative targets, check both biochemical markers (protein aggregation, synaptic function) and behavior (cognitive tests). Converging evidence from different angles is the final proof that a comparative hit is biologically meaningful.

*You might have noticed this has come up a lot. It is fundamental and logical to validate typologies orthogonally and it highlights and acknowledges the importance of context.

This is the third piece in the “Betting on Biology” series. At this point, we have talked about the major target identification approaches. In the next piece, we will think about the important questions to ask in deciding the targets: How should we test directionality? How do we prioritize evidence? What are the killer tests to consider? See you soon.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to Satvik Dasariraju for the inspiration, thoughtful comments, and prompt answers to my many questions; to Alex Colville for invaluable writing guidance throughout the process; and to every age1 crew for helpful pointers. Special thanks to Gordian, Fauna, and the amazing founders for the inspiration. Cheers!